The Returnees. How veterans of the war in Ukraine are killing and maiming Russians

More than a thousand people have fallen victim to soldiers returning from the front

Nearly four years into Russia’s war against Ukraine, soldiers returning from the “SMO” have killed and injured more than 1,000 people. Most of the victims are the military’s own relatives and acquaintances, and the crimes are typically committed during bouts of heavy drinking.

At the request of several individuals, some names in this story have been changed

To read future texts, follow us on Telegram

Farid and Anna came home on the morning of June 16, 2025, after Farid’s shift at the OZONi warehouse. They decided to have a drink. When the alcohol ran out, Anna went to the store and came back with friends. Farid didn’t like that — he kicked the guests out and started an argument.

During the fight, he grabbed a scarf from the hallway and strangled Anna, then hid her body in the refrigerator. He also killed her barking cocker spaniel and threw the dog into the bathtub. Afterwards, he kept drinking.

That evening, Farid took Anna’s Apple Watch and phone and left the apartment. Her body remained in the refrigerator for another three days.

Just a few months earlier, Farid had returned to Noyabrsk (a city in Western Siberia) as a “war hero.” He had been recruited to fight in Ukraine straight from a penal colony, where he was serving a 15-year sentence for murdering an acquaintance.

Murders, beatings, and deadly crashes

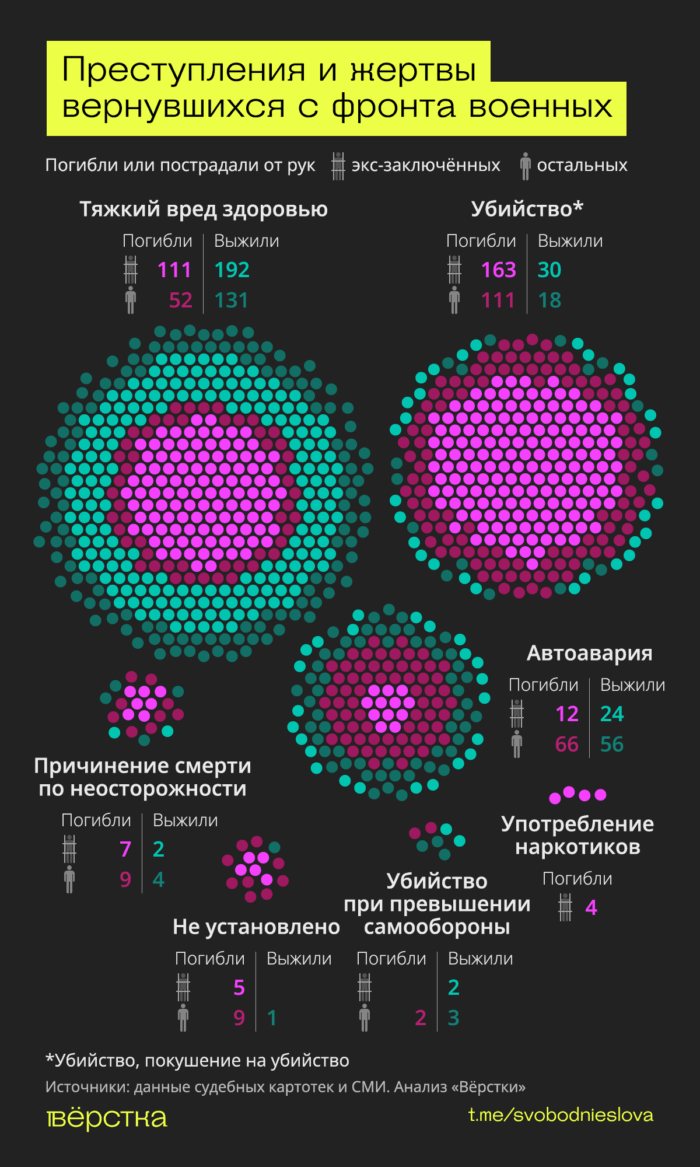

Crimes like these are far from rare among those returning from the so-called “special military operation” (“SMO”) zone. Over nearly four years of war, they have committed 240 murders — the most common fatal offense among veterans of the war in Ukraine. According to Verstka’s calculations, at least 551 people have died at the hands of returning soldiers. And that is not the full picture: many victims survived but were left with serious injuries or permanent disabilities — at least 465 people.

In total, the number of victims of Russian participants in the war in Ukraine now exceeds one thousand. Most of those killed were relatives or acquaintances of the veterans; the majority of crimes were domestic and happened in the context of alcohol abuse.

How we calculated this

For its analysis, Verstka examined media reports and court records, identifying more than 900 criminal cases involving military personnel. These included cases under the following articles: Murder; Causing death by negligence; Murder committed in excess of necessary self-defense; Intentional infliction of grievous bodily harm; Infliction of grievous bodily harm in excess of necessary defense; Infliction of grievous bodily harm by negligence; Violations of traffic rules and vehicle operation; Inducement to use narcotic or psychotropic substances.

We also counted crimes in which no public criminal case could be confirmed — for example, when the perpetrator committed suicide — but only when participation in the “SMO” could be independently verified.

Cases where the suspect’s involvement in the “SMO” could not be confirmed were not included.

The final dataset includes only crimes committed by individuals who returned to Russia, annexed Crimea, or South Ossetia after taking part in the “special military operation”:

— 521 pardoned or conditionally released former prisoners, and

— 397 regular military personnel — those who returned home on leave, after being wounded, after completing their contracts, or after being discharged.

Over nearly four years, at least 551 people have died as a result of “fatal” crimes committed by men returning from the war:

- 274 people were killed in 240 murders (Article 105 of the Russian Criminal Code; in some cases, the charge covered the murder of two or more people).

- 163 people died after sustaining serious bodily injuries (Article 111).

- 78 people were killed in road accidents, which resulted in 58 criminal cases for traffic violations (Article 264).

- 16 people died in 13 cases of negligent homicide (Article 109).

- Four people — including two minors — died in three cases of incitement to drug use (Article 230).

- Two people were killed in cases classified as exceeding the limits of necessary self-defense (Article 108).

- Fourteen people died in incidents for which no criminal case was opened or for which the applicable criminal article could not be determined.

“He already paid for that crime with his blood in the ‘SMO’”

According to Verstka’s analysis, more than half of all those killed — 163 people — died at the hands of ex-convicts. Of the 281 previously convicted soldiers who, after returning from the front, killed again or caused injuries that led to death, at least 142 had earlier served prison terms for similar violent crimes.

In June 2025, residents of an apartment building in Noyabrsk (a city in Western Siberia) complained to the police about a strong, foul smell in the stairwell. When emergency services opened the apartment in question, they found the body of a dog among piles of scattered belongings. The dead animal, covered with rags and sprinkled with detergent, was decomposing in the bathtub.

Officers then turned their attention to the refrigerator in the kitchen — it was tied shut with two scarves, and bloodstains were visible on the outside. Inside was the body of a young woman in a bathrobe.

A few days earlier, neighbors had heard loud noises and the barking of a dog coming from the apartment of 33-year-old Anna Kasyanova. Residents also recognized the man seen in the stairwell shortly before her death — a person they believed to be her boyfriend, who had first appeared at the building in May 2025.

Police soon detained him. It turned out to be 37-year-old Farid Khalimov.

According to the case file, Khalimov met Anna a month before the killing: on May 9, 2025, a childhood friend had brought him to her apartment, and the two stayed in touch afterward.

Khalimov told investigators that he sometimes spent the night at Anna’s apartment.

But Anna Kasyanova’s friend, Marina Leonova, gave Verstka a different account. She said Anna and Khalimov were introduced by a mutual acquaintance — Andrei, Anna’s partner. In early 2025, Andrei was sent to a penal colony for illegally registering migrants (Verstka could not locate the court ruling, as Marina did not disclose Andrei’s full name). Before leaving, Andrei asked his friend Farid Khalimov to “keep an eye on” Anna while he served his sentence.

“He arrived in Noyabrsk as a hero — he’d been through the meat grinder and survived,” Marina said. “Andrey asked Farid to look after Anya, to make sure she behaved,” she told Verstka.

Marina described Anna as “impulsive” and “cheeky.” When Andrei asked Farid to watch over her, Khalimov simply decided to move into Anna’s apartment:

“Her mother had died not long before. It hadn’t even been a year. She lived alone, and he just showed up and said, ‘Well, that’s it — I’m living here now,’” Marina recalled.

According to Khalimov, on the morning of June 16 he became jealous when Anna returned from the store with two new acquaintances. He said he kicked the men out and began arguing with her. He claimed that during the fight, he took a scarf from the hallway, wrapped it around Anna’s neck as she lay on the bed, and strangled her.

Anna’s friend gives a different account. She says that earlier, Anna had thrown Khalimov out of the apartment — and when he came back again, she already had friends over.

“He came in, kicked her friends out, and she started yelling at him, ‘Why did you kick my friends out? Who do you think you are?’ And Khalimov was already drunk. That’s when he strangled her,” the friend said.

Wanting to make sure Anna was “definitely dead,” Khalimov took a wooden mallet from the kitchen and struck her on the head eight times. Then, “so the body wouldn’t rot,” he emptied the refrigerator, placed her inside, and tied the door shut with scarves to keep it closed. After that, he stayed in the apartment drinking until late evening. Before leaving, he took Anna’s smartphone and Apple Watch.

Marina says she knows that Khalimov had left the penal colony — where he was serving a sentence for murdering and dismembering a police officer — to join the “SMO.”

“They tried to arrest him on a drug charge, Article 228, but he killed the police officer and dismembered him. I don’t know — it seems he got a fair sentence, ten years. Then he filed a petition — basically signed a contract — saying he wanted to go serve in the SMO,” Marina says.

The court documents do not contain such details. According to the Supreme Court, in 2015 Khalimov was sentenced to 15 years in a high-security colony for murdering an acquaintance. In June 2014, the two had been drinking when the man insulted Khalimov and his friend, prompting them to beat him. When the victim threatened to go to the police, Khalimov stabbed him several times, and his accomplice struck the man on the head with an axe.

The sentence for the second murder turned out to be much lighter. For killing Anna Kasyanova and theft, the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (a region in Siberia) court sentenced Khalimov to eight years and one month in a high-security colony. The court treated his combat service and state awards as mitigating factors.

Marina was shocked when Verstka told her that Khalimov had received an eight-year sentence.

“I even asked the police, ‘Isn’t this a repeat offense? He killed someone and even dismembered him.’ And they told me, ‘No — he already paid for that crime with his blood at the front, he was pardoned.’ So if he hadn’t been pardoned back then, of course the sentence for killing Kasyanova would have been longer,” she said.

“So that she suffers”: ex-convicts kill more often than others

On the evening of April 4, 2025, a 45-year-old woman with burns covering nearly her entire body — including her mouth and respiratory tract — was brought to the intensive care unit of the Kaban District Hospital in Buryatia (a region in Eastern Siberia). Doctors fought for her life for a week, but she did not survive.

She lived with 39-year-old Sergei Korytov, who scraped by doing odd jobs and drank heavily. During his drunken outbursts, he often beat his partner. On April 4, after buying several bottles of vodka, Korytov was drinking at home with her when an argument broke out. The woman decided to throw him out, but instead of leaving, he grabbed a canister of oil and gasoline and, as he later told the court, “decided to kill her, wanting her to suffer.”

He poured the liquid over her as she sat on the sofa and set her on fire. After some time, he extinguished the flames and called for medical help. When the doctors arrived, they found the woman sitting on the sofa in charred leggings. A drunk Korytov remained calm, insisting that she had been injured while trying to light the stove.

For the especially cruel murder, a court in Buryatia sentenced Korytov to 16 years in a strict-regime prison — while still treating his participation in the “SMO,” his military awards, and his injury as mitigating circumstances. He had gone to war straight from prison, enlisting with the Wagner PMC, for which he received a presidential pardon. Before that, Korytov had been convicted of rape, and in 2019 he received a 14-year strict-regime sentence for gang robbery and inflicting grievous bodily harm resulting in death.

More than a third of the former inmates had been convicted of murder before, and another 31 of the 148 previously convicted contract soldiers had already served sentences for causing grievous bodily harm resulting in death. Sentences handed down to former prisoners now range up to 14 years, while other soldiers have received up to 12. In cases involving particularly brutal killings or the murder of multiple victims, courts have issued sentences of up to life imprisonment.

The first to receive a life sentence, according to Verstka, was Grigory Starikov, who murdered two male acquaintances and one woman with a crowbar. Others on this list include: Adam Shcherbakov, who killed a father of a famous priest, Father Vladimir Legoyda, during a robbery; Oleg Grechko, who burned his sister alive; Ruslan Shingirey, who raped and murdered an eight-year-old girl; Vladimir Alexandrov, who raped and murdered an eleven-year-old girl; and Igor Sofonov, who, together with an accomplice, killed seven people.

“I’ve beaten and I’ll beat again”: relatives and acquaintances are the ones most often harmed

According to people who knew him, 26-year-old Vladimir Moksheev from the village of Shchebzavod in Kemerovo (a city in southwest Siberia) had always been withdrawn and quick to anger. He kept to himself at school, was rude to teachers, and performed poorly academically.

“His whole family was strange — his parents would go on drinking binges. They didn’t look after him, he had to repeat a grade, and eventually they transferred him to a special school,” one of his former classmates told Verstka.

Maria Ravodina lived next door to Moksheev. She had gone to the same school and was three years younger than him. Her family was large and troubled. After her mother was killed (Verstka was unable to independently confirm this), acquaintances say 16-year-old Maria was left on her own. Not long after, she had her first child with 19-year-old Moksheev. Three more children followed.

“They lived poorly. Both of them drank, the kids were always dirty, nobody taught them anything. The oldest is eight and still doesn’t talk. It’s a completely antisocial family,” one of Verstka’s interlocutors says.

According to him, Vladimir and Maria drank constantly, and she suffered regular abuse. Court records show that in 2021 Moksheev was held administratively liable for battery.

“Vladimir drank and beat Masha. Always. They both drank. Then he went to the ‘SMO,’ and Masha was left alone with the kids — fighting, drinking, the children always dirty and hungry. Neighbors called child protective services more than once. But nothing happened: the father was in the military, so they were ‘untouchable.’ That went on until Vladimir came home on leave,” recalls a former classmate.

In September 2024, after being wounded, soldier Vladimir Moksheev returned to the Kemerovo region. On December 22, 2024, the family was drinking at home, and Maria’s brother, Ivan Ravodin, was visiting. A quarrel broke out, and Moksheev stabbed his guest to death. The couple’s small children were in the house during the killing. Afterward, they were taken into state custody.

“Vanya was a good guy. Unlucky, withdrawn, yes — but a good person who never hurt anyone. He had been working since he was fourteen,” an acquaintance told Verstka.

Moksheev was convicted of this murder in June 2025, but the verdict was not published on the court’s website. But, according to acquaintances, after the murder, the man was sent back to war. The children were soon returned to their mother. “Their father is an ‘SMO’ participant, you can’t touch him,” explained acquaintances.

For almost four years, the victims of “SMO” members have most often been people from their own circle: acquaintances and relatives. The reasons for the murders are family or domestic conflicts.

“This is what happens to those who don’t pay us back,” said volunteer of the StormV unit from Orenburg (a city in southwest Russia), Maxim Trifonov, who beat an acquaintance to death for joking about his cooperation with the prison administration. He received 8 years.

“Looking for a life partner…” — this was the status posted on his VKontakte page by PMC Wagner soldier Petr Sevalnev from the Tyumen region (a region in Siberia). After returning from the war, he beat his partner to death in a fit of jealousy. He received 8.5 years.

“Where are you going? I’m not finished talking!” shouted Kirill Kyzyma, an “SMO” participant from the Chelyabinsk region (close to Ural Mountains). His attack on his former girlfriend was caught on video by a witness. Kyzyma killed the woman after she refused to get back together with him and marry him. He was sentenced to nine years in prison.

“At a certain moment, he formed the intent to kill him, despite having no conflict with her,” the court ruling states. Artem Podkorytov, an ex-convict from Omsk, murdered a new acquaintance while drunk. The man had invited him over, fed him, and offered him a place to stay for the night. Podkorytov received nine and a half years.

“I’ve beaten and I’ll beat again”, said Dmitry Efimov, an “SMO” veteran from the Perm region (close to Ural Mountains) who beat his own mother to death because she had been drinking. He received a 10-year sentence.

“I’m sorry, I killed him because he insulted me,” said Vladimir Shishnev, an “SMO” participant from the Transbaikal region who murdered a co-worker for making “bad comments” about “SMO” soldiers. He was sentenced to ten years.

“I just wanted to deprive her of her natural beauty”: most sentences for grievous bodily harm are suspended

In addition to the 551 fatalities, the dataset includes 465 people who were seriously injured by returning “SMO” veterans. All of them sustained grave injuries, some were left disabled, but survived:

- 318 cases of life-threatening grievous bodily harm (Article 111 of the Russian Criminal Code), resulting in 323 victims;

- 41 attempted murders (Article 30 Part 3, Article 105), with 48 victims (cases with no harm, minor harm, or unclear harm were excluded);

- 56 traffic accidents (Article 264), in which 80 people were seriously injured;

- 5 cases of “exceeding the limits of necessary defense” (Article 114), resulting in 5 seriously injured victims;

- 6 cases of causing serious harm through negligence (Article 118), with 6 victims;

- 1 fatality from a crime for which the criminal article could not be established.

More than half of the victims, 252 people, were harmed by former prisoners. One of them was Dmitry Voronin from the Tver region (a region in Central Russia). In 2022, he was serving time for theft, but enlisted with the Wagner PMC, went to fight in Ukraine, and returned home in 2023. He drank heavily and periodically beat his mother who was also an alcoholic addict. In 2024, he received two new convictions: for threats to kill and for causing moderate bodily harm. In October that year, he punched his mother nine times in the head and torso because she was drunk. She was hospitalized with a brain hemorrhage and fractures. Voronin was sentenced to 2 years and 9 months in a general-regime colony.

Most cases stem from domestic conflicts, half of them involving alcohol or drugs.

One example: Valery Patrakeev from the Stavropol Krai (a region in Southern Russia) assaulted his sister-in-law, who came to visit for Easter in 2024. She reproached him for mistreating and not helping his wife. Patrakeev had lost a leg in the war and used a wheelchair. But after her criticism, he stood up, saying: “You think I’m disabled and can’t do anything?” He then broke her arm, causing a displaced fracture of the humeral neck and threw her across the table. A regional court gave the veteran a three-year suspended sentence.

Almost one-third of all Article 111 cases ended with suspended sentences, according to Verstka’s analysis. Among former prisoners, only 21% (40 out of 189) received suspended sentences, while among other military personnel, the share was 49% (63 out of 129).

In more than 50% of cases, combatants used improvised “weapons”: knives, sticks, bottles, crowbars, shovels, axes, pipe sections, frying pans, scissors, beer mugs, stools, traumatic pistols, and more. Such attacks tend to cause more severe injuries.

When courts do impose real prison terms under Article 111, “SMO” veterans typically receive between one and seven years, according to Verstka’s analysis.

The most widespread crime among veterans is still the intentional infliction of grievous bodily harm dangerous to life. Returning soldiers have committed at least 482 such offenses, leading to 163 deaths and 325 injuries, including cases resulting in disability.

Take the case of former prisoner Sergei Popravko. He walked into a Pyaterochka supermarket (a low-cost grocery chain) and tried to steal a bottle of vodka, hiding it under his clothes. The store manager’s husband saw the theft on the security cameras and demanded that Popravko put the bottle back. In response, the intoxicated Popravko punched him in the head. The man lost his balance, fell, and struck his head on the floor, suffering a closed head injury and a brain contusion. He later died at home. The court sentenced Popravko to seven years in a strict-regime colony.

This was his second conviction in his otherwise “clean” post-war biography — after returning from the front, he had already served nearly a year and a half for theft and robbery. Popravko most likely enlisted straight from prison, where he had been serving yet another sentence for theft since 2022. His contract allowed him to “wipe clean” his criminal record.

Another 48 survivors suffered severe injuries as a result of attempted murders, 80 were seriously injured in traffic accidents, and 11 were injured due to excessive self-defense or negligence.

Over almost four years, “SMO” participants committed 114 crimes involving traffic violations and vehicle operation, resulting in 78 deathsi.

Soldier Alexei Zatsepin was behind two such incidents — one in annexed Crimea and another in Krasnodar Krai (a region in Southern Russia). After going AWOL for nine months, he caused two serious traffic accidents with multiple casualties.

In July 2024, Zatsepin was driving an Opel Vivaro minivan from Kerch to Simferopol (cities in annexed Crimea) when he fell asleep at the wheel and slammed into a Scania truck parked on the roadside. Three of his passengers were killed, including a 16-year-old girl, and two others were seriously injured.

Four months later, in the Krasnodar region, he caused another crash. While driving in Sochi (a resort in Southern Russia), Zatsepin veered into oncoming traffic and collided with another car. The other driver suffered severe injuries and had to be cut out of the mangled vehicle.

For both incidents, the Sevastopol Military Court sentenced Zatsepin to seven and a half years in a general-regime colony.

Alcohol fuels aggression among returning veterans

In November 2024, paramedics were called to the Magadan (a city in Russian Far East) Center for Social Services for the Elderly and Disabled. In the hallway outside the kitchen, they found Alexander, a young man with a blood-soaked bandage wrapped around his left thigh. Inside the kitchen sat another young man in a wheelchair, both of his legs amputated. Blood spattered the walls, and a pool of blood mixed with shards of broken dishes covered the floor.

The wheelchair-bound man told the medics that Alexander had supposedly cut himself on a broken piece of glass. But it was already too late: the wound had severed the femoral artery and vein, and Alexander had lost too much blood to be saved.

Just a few hours earlier, he had come to visit his childhood friend — 26-year-old Dmitry Inylyv, a resident of the social center.

He had enlisted from a penal colony, where he’d been serving a sentence since 2022 for causing grievous bodily harm, fraud, and document theft. After being seriously wounded in the war and losing both legs, he received a presidential pardon and returned to Magadan, where he lived in a social care facility.

That evening, Dmitry and Alexander were drinking in the center’s kitchen along with three acquaintances. When the others went to bed, only the two childhood friends remained. Their conversation didn’t last long — about half an hour later, the heavily intoxicated Inylyv grabbed a knife from the table and stabbed Alexander, interpreting something his friend said as a real threat. Hearing the crash of dishes and the struggle, the others rushed back into the kitchen and saw Inylyv sitting in his wheelchair, while Alexander lay on the floor, bleeding heavily. They dragged him into the hallway, tried to give first aid, and called an ambulance.

The Magadan court sentenced Inylyv to five years in a high-security colony for intentionally causing grievous bodily harm resulting in death. His veteran status and first-degree disability were counted as mitigating factors.

Intentional infliction of grievous bodily harm resulting in death is the second most common crime committed by “SMO veterans,” after murder. At least 64% of such cases in Verstka’s dataset involved alcohol: 72 among former prisoners and 26 among other military personnel. Yet courts did not always treat intoxication as an aggravating factor — it was noted in only 26 cases. Sentences handed down so far range from 4 to 11 years for both pardoned ex-prisoners and other fighters.

Only nine of the 163 cases were linked to theft, robbery, or carjacking — and most of these were also forms of domestic violence within the veterans’ immediate circles. Women were significantly less likely to be victims of grievous bodily harm resulting in death: 19 of 111 cases among ex-prisoners and 8 of 50 among other combatants.

Participation in the “special military operation” almost always reduces the sentence

Ruslan Gusarov, a repeat offender from the Murmansk region (a region in Northern Russia close to Norway) previously convicted several times for theft, was sentenced in 2016 to 9.5 years in a high-security colony for drug distribution. While in prison, he was recruited by the Wagner PMC, sent to fight, and soon returned home.

One evening, while drinking with a friend, Gusarov began talking about the war in Ukraine. The host showed him a non-functioning airsoft rifle that resembled a Kalashnikov. When Gusarov asked to take a look, the man refused — and was stabbed three times in the chest and abdomen. He died from his wounds.

A Murmansk court initially sentenced Gusarov to eight years in a high-security colony. But he petitioned the court to recognize his participation in the “SMO” as a mitigating factor. The sentence was overturned on appeal, and during the new trial the judge indeed took his military service into account, reducing the term to 7.5 years.

Verstka’s analysis of more than 700 published court rulings shows that in over 90% of cases, judges considered participation in the “SMO” a mitigating circumstance. Fewer than 10% of rulings ignored this factor. In addition to direct participation in the operation, courts also cited “state awards,” “combat injuries,” “combat veteran status,” “service in defense of the Fatherland,” and similar phrases as grounds to reduce sentences.

Another frequent justification for leniency is the “unlawful” or “immoral” behavior of the victim — courts treated this as a mitigating circumstance in nearly a quarter of the cases.

By contrast, judges often ignored alcohol as an aggravating factor. Of the 486 sentences involving intoxication handed down to pardoned or paroled ex-convicts returning from the war, which Verstka was able to examine, courts declined to count alcohol or drug intoxication as an aggravating circumstance in 326 cases.

“What will happen when they are all released?”

The real number of crimes committed by “SMO” veterans that resulted in casualties is significantly higher than what Verstka was able to include in its sample. Since the start of the war, garrison courts have almost entirely stopped publishing rulings and press releases about such cases, even though crimes committed by combatants have increased sharply compared to pre-war statistics.

Courts also often withhold important information when they do publish decisions: references to presidential pardons, personal data of defendants, or any mention of their participation in the “SMO” may be removed. In some cases, previously published rulings are deleted altogether.

Meanwhile, the share of veterans who have actually returned to civilian life remains relatively small. Even if we take the authorities’ official statements at face value, no more than 140,000 service members have come back from the front.

This is a small group relative to Russia’s male population — and yet, the rates of serious crime among them are dramatically higher. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Russia recorded 7,332 murders in 2021; 84% of crimes are committed by men. Converted into a per-capita rate, this equals 9.25 murders per 100,000 men per year.

Among approximately 140,000 returning veterans, there have been at least 240 murders in under four years — or 171 murders per 100,000 people. The number of victims is even higher: 195 per 100,000.

In other words, the murder rate among veterans is more than five times higher than among Russian men overall.

Marina, the friend of Anna Kasyanova, who was murdered in Noyabrsk, worries about what will happen next:

“Can you imagine what will happen when all those prisoners who went to war are released? Even the Bitsa Park Maniaci — he also wants to go to the SMO. Fifty-eight peoplei! If they release people like that, I don’t know what will happen to the country. To Russia. It’s a nightmare.”

Cover: Alisa Kananen

Поддержать «Вёрстку» можно из любой страны мира — это всё ещё безопасно и очень важно. Нам очень нужна ваша поддержка сейчас