“Bring a friend”: How Russians earn money by sending each other to war

From local kingpins to women on maternity leave — many are now persuading people to sign contracts with the Ministry of Defense.

Recruitment for the war in Ukraine has grown into a multi-level system that involves a wide range of Russians. Verstka explores how — and how much — women on maternity leave, local kingpins, career military officers, and former HR workers earn by persuading men to sign a contract with the Ministry of Defense and head to the front.

Some names in this story have been changed for safety reasons.

To read future texts, follow us on Telegram

“I’d like to sign a delivery slip.”

In the fall of 2024, at the checkout of a grocery store in Lipetsk (name of the city changed), two men stood in line to buy water and cigarettes. Konstantin — a sturdy, gray-haired man and a high-ranking regional official — was paying.

“What a rip-off,” muttered the second man, Artur, dressed in worn-out clothes and smelling of alcohol, staring at the 80-ruble (less than 1 EUR) bottle of water.

They then got into a black SUV and drove toward the city’s industrial district, lined with five-story Brezhnev-era apartment blocks.

“There’s a chance to change your life,” Konstantin told him as he drove. “What do you have now? You’re alone, unemployed, broke.”

Artur didn’t argue. For months he had been drinking heavily and borrowing money from anyone who would lend it. That same morning — despite meeting Konstantin for the first time — he had already managed to borrow five hundred rubles (slightly more than 5 EUR) from him.

The men entered one of the district’s brick buildings, where they were greeted “like honored guests” and served out of turn. None of the people visiting the Lipetsk military registration and enlistment office that day came there voluntarily to serve — except for Konstantin and Artur, who had come for that exact purpose.

“I was afraid they wouldn’t let us in — the guy was clearly unfit, a real down-and-out type. But the staff member said, ‘Wonderful,’ and told us to bring him in,” Konstantin recalls. “My friend began to mumble, ‘I haven’t decided yet.’ And she told him, ‘How can you not have decided yet? Who will defend us?’ She spoke so convincingly that anyone would have signed up.”

While the unemployed man was being told about the payments and his “sacred duty,” the official stepped into the office of the deputy military commissar.

“I need to sign a delivery slip,” he said — and immediately received the document. Konstantin was to be paid 50,000 rubles (approx 530 EUR) for “delivering” the candidate, as long as the recruit passed the medical exam and actually went to war.

The official left to take care of other business, hoping the recruit wouldn’t “back out,” and aired out the car after dropping him off.

“No one promised him things would turn out fine.”

Over the years of the war, recruiting Russians for the front has grown into a bustling marketplace — one in which a single signed contract can involve both a “client” and a “contractor.” Thousands of men who go off to fight end up helping regional and municipal agencies, as well as state enterprises, meet their KPIs — often without even realizing it.

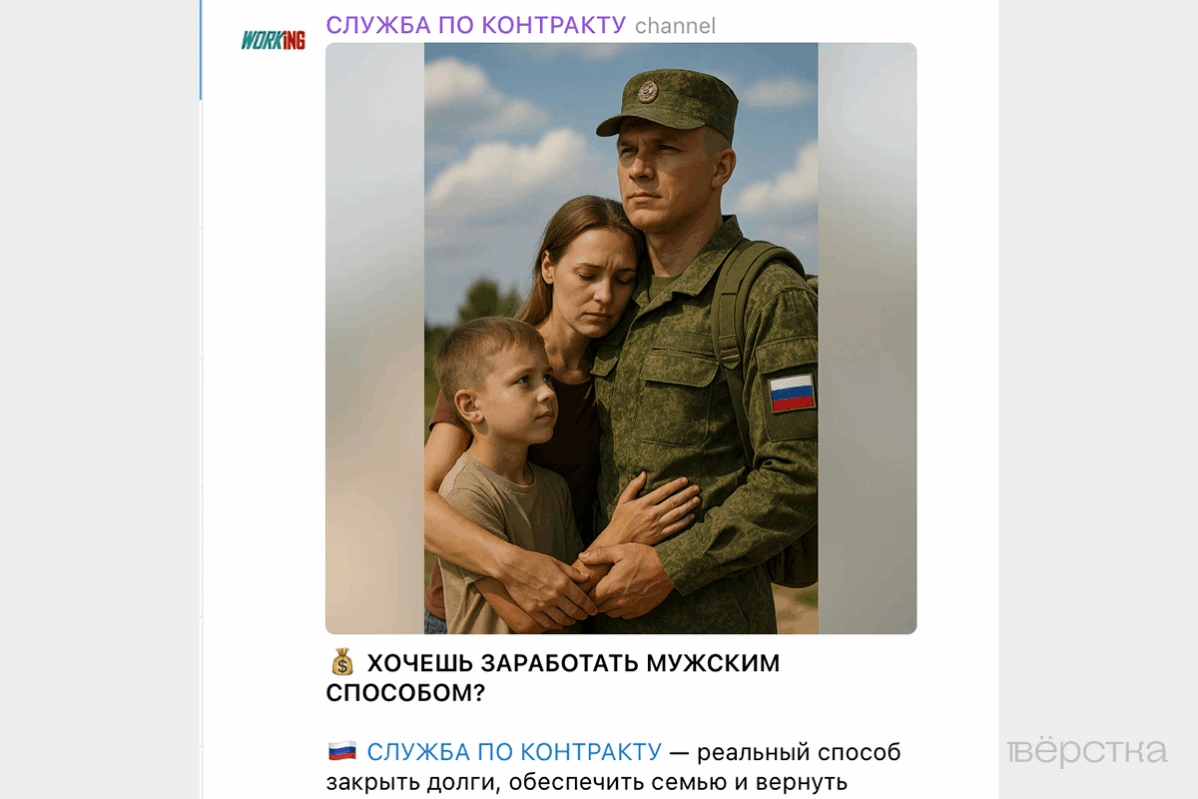

When scrolling through Telegram posts or chatting with neighbors about increased “SMO” payments, a man may have no idea that recruiters are already competing for him as a potential “client.” These recruiters might be former HR managers now working with enlistment offices through intermediaries, mothers on maternity leave who have mastered eye-catching ad design, or simply people with large social circles and a knack for persuasion.

Whoever proves most persistent and successfully delivers the candidate to the front — earns a commission: anywhere from 5,000 to 350,000 rubles (approximately 50–3700 EUR), depending on the client’s status.

This is how Artur ended up in the car of a Lipetsk official who was taking him straight to the military enlistment office. The previous day, local authorities had been given a recruitment quota, and Konstantin, who also had his own KPI (four recruits per month), turned to a recruiter. The service was provided by a “local kingpin.”

“He found me a suitable guy — Artur — and I decided to go through the whole chain myself so I could later scale the scheme,” Konstantin recalls. “There’s no deception here. The guy could have drunk himself to death. I told him: ‘Look, you’ll get money. You’ll come back a respected man — if you come back.’ No one promised him that there were no risks or that everything would be fine.”

But the candidate never showed up for the medical examination — he “dropped out.” Later, according to the official, another recruiter met with Artur, but he also didn’t send him to the front: Artur was registered at a psychiatric clinic and wasn’t eligible for service.

“They told me he could be taken off the register,” Konstantin says. “But I didn’t see any motivation in him. Why bother in that case? From the start I was thrown off by the fact he asked me — and the enlistment office staff — the same thing: ‘Can I sign the contract later, but get at least five thousand rubles now?’”

Fixers and coffee with a bun

Employees at military enlistment offices say they see recruiters every day — and can spot them instantly. Yaroslav, a Moscow City Hall employee who works at the Unified Recruitment Center, sends a photo of a young woman in a burgundy suit with a matching leather bag, talking on the phone in front of a sign reading “Fluorography.”

“They’re mostly women — ‘successful young ladies’” Yaroslav says. “They stand around scanning the room, walking arm in arm, and they’re dressed inappropriately flashy, like escorts. You can tell immediately they’re not our staff. If someone’s wearing sneakers, loose pants, has a belly and a pack of cookies — that’s one of ours. But if it’s tight miniskirts and bright lipstick, who the hell knows. We see them as spiders whose job is to catch someone. And the web is spread over different stages: some people are caught in another city, some get their tickets bought for them, some are found at work.”

“These guys are always on the move — hustlers, fixers,” says Dmitry, a serviceman who trains recruits in one of the Far Eastern regions. “They talk to everyone: middle-class men, people on the margins, drug addicts, guys they once did time with. They have a buddy in every car repair shop.”

Dmitry says he already recognizes some recruiters by face — and knows their backstories. One is a local government official who frequents the enlistment office and helps both his bosses and city agencies meet their quotas. Another is a former PMC Wagner fighter who returned from the front and now recruits “on the side” for extra cash.

Customers — whether state institutions or local officials — are willing to pay for a candidate guaranteed to count toward their quota.

“Say a man was thinking about signing a contract on his own, but his supervisor caught him and brought him to the police,” Yaroslav explains. “He has a credit card, and they fabricate a story that he’s in debt and wanted by court officers. The security forces get their ‘tick,’ and the man goes to the front as a debtor.”

“They’ll push you through every commission just to have you signed under a specific organization,” Dmitry adds. “It could be the city’s electrical grid, the water utility company — even a kindergarten.”

Recruiters, he notes, rely heavily on the desperation of their candidates — often men burdened with loans or debt — who don’t question their intentions and instead interpret everything as an act of kindness.

“While they’re sitting in line, the recruiter brings them coffee and a bun. And for many of these men, no one has ever spoken kindly to them in their lives. It’s just… honestly, it’s terrifying to watch,” Dmitry says. “One case was completely insane — recruiters brought in the same man with hepatitis five times. I looked at his passport and said, ‘You’re unfit!’ And the recruiter insists, ‘It’s his first time here!’ They thought we didn’t remember people and tried to pass him off as a newcomer. I wouldn’t be surprised if they eventually pushed him through somewhere else.”

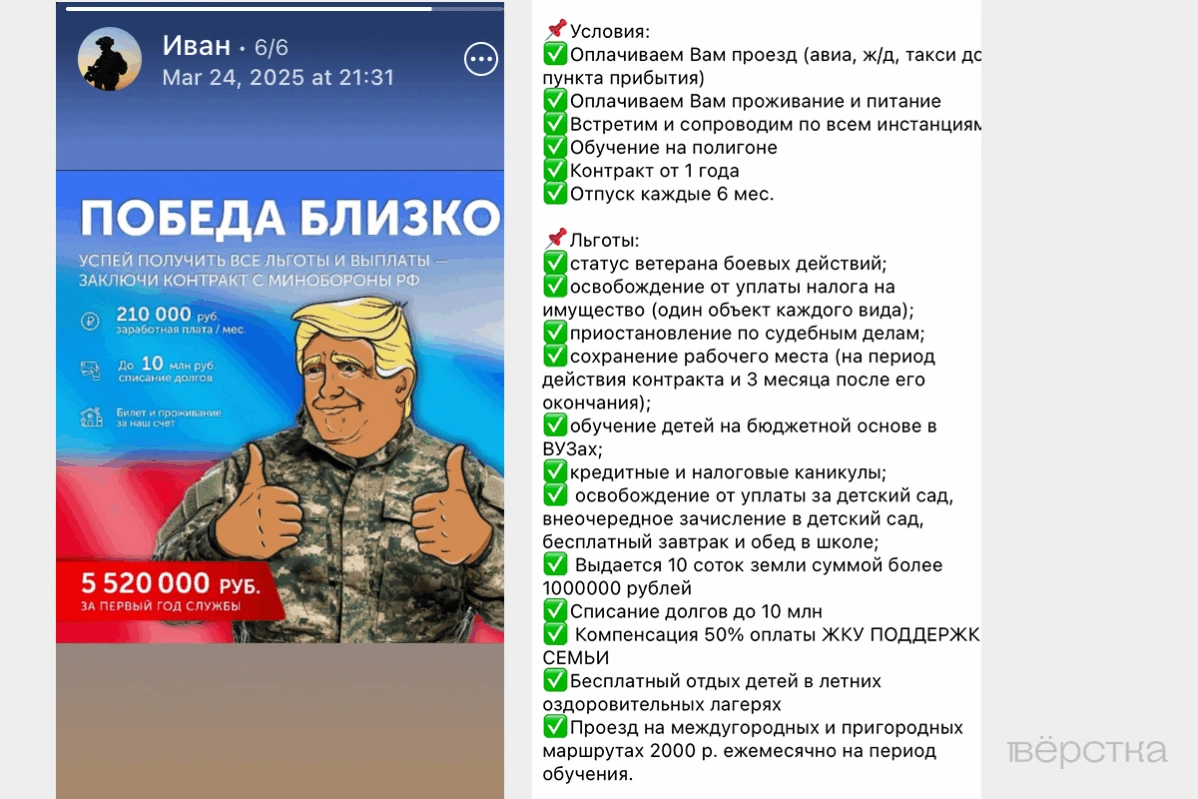

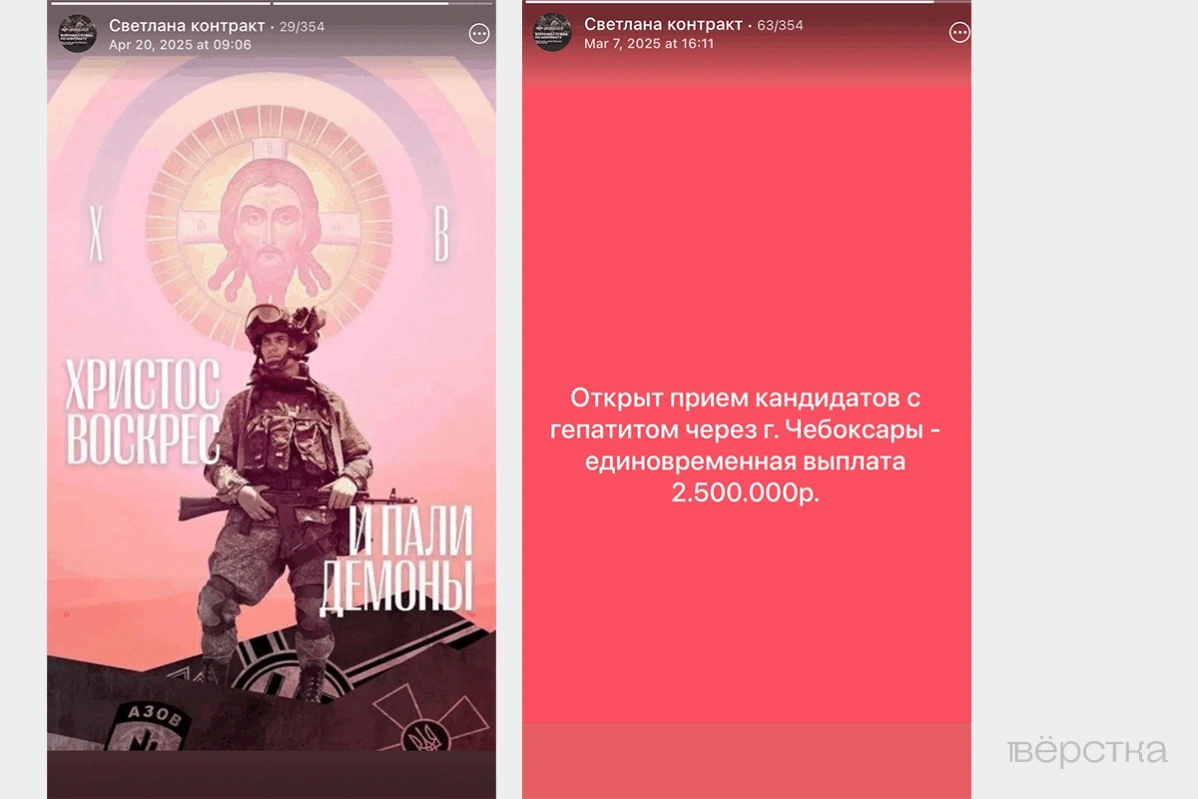

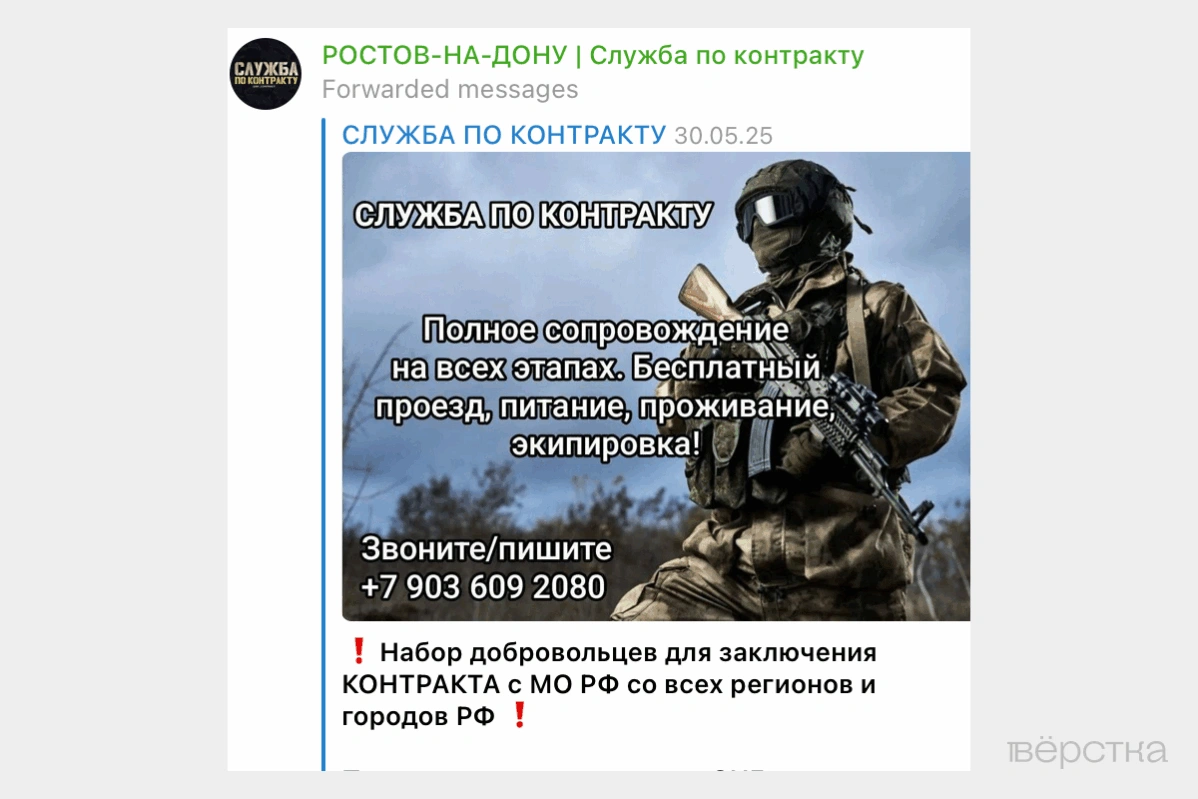

Intermediaries offer recruitment across different regions, where compensations and benefits vary. Telegram channels serve as a marketplace: posters advertising pay rates, perks, and the phone numbers of curators appear every hour.

These ads often create the illusion that even war can be navigated safely with the right “connections.”

Olga promises drones’ operator courses in Yaroslavl.

Andrei offers rear-area driver positions.

Georgy guarantees a vacation every six months.

They’ll pay for plane or train tickets, provide three meals a day, and arrange accommodation during medical checks. But most of them will never actually meet the people they recruit.

This is how another category operates — remote recruiters who recruit for the war entirely online.

“Individual support and security”

“I don’t know what happens to them afterward. My job is to get them to show up and sign the contract. We don’t stay in touch — there’s no connection once that’s done.”

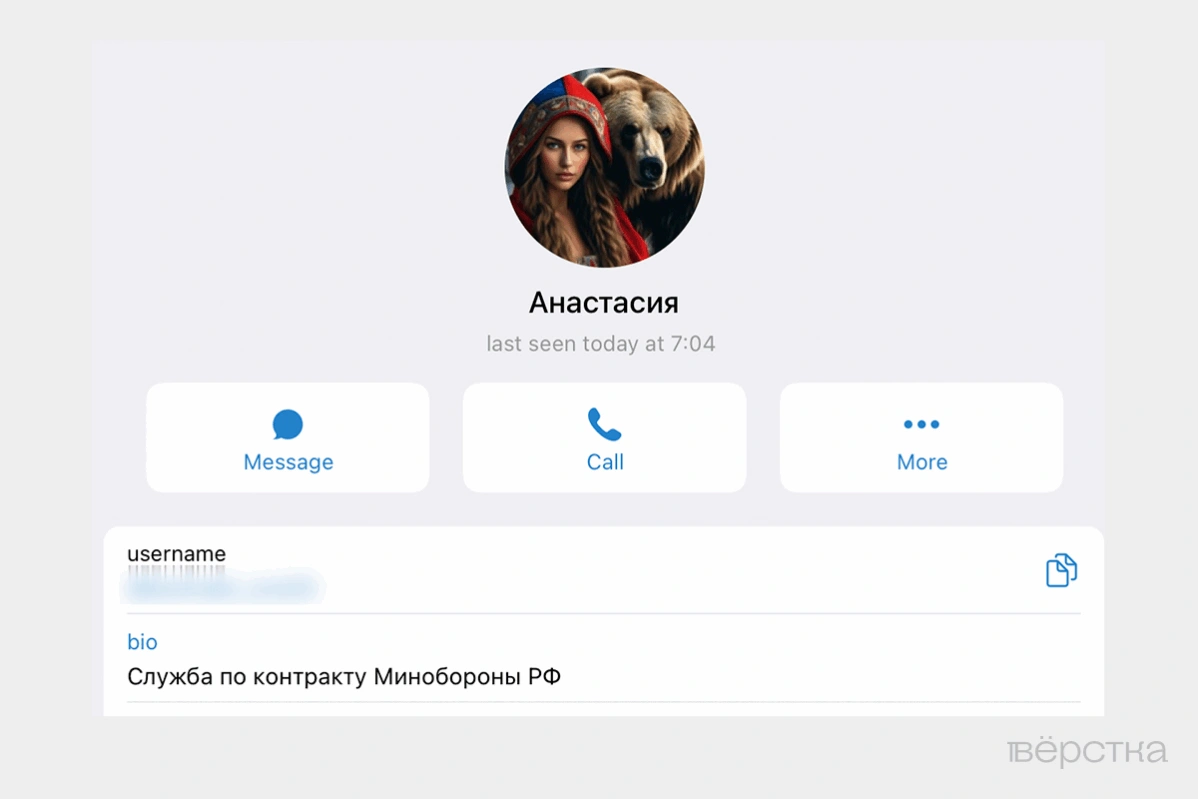

Verstka messages with a recruiter named Victoria. Her avatar shows a blonde woman with long false eyelashes and a low-cut top. On Telegram, she advertises contract service as “a worthy choice for a patriot,” decorating her posts with pictures of a soldier in a helmet and vest.

Vika promises that, through her, it’s possible to sign a contract even without a military ID — and even while registered with a drug treatment clinic, or having hepatitis, HIV, or a criminal record.

She also guarantees a long list of benefits: older children admitted to university on state-funded places, younger children receiving free spots in summer camps, family debts of up to 10 million rubles (more than 100 thousands EUR) written off, a 10-acre land plot, and suspension of any court cases. And these are only some of the perks she advertises.

Dozens of men call and message Victoria every day. None of them know which city she lives in — or what the real person behind the fake blonde photo looks like.

“Do you accept women?” Verstka replies to her ad.

“No.”

“If any of my male friends want to sign a contract, can I give them your number?”

“I’d be grateful. I’ll transfer 10,000 rubles (more than 100 EUR) for each candidate,” Vika suddenly offers, adding that no one is being sent to the “red zone” anymore because “the war is ending.”

Verstka asks Victoria about the nature of her work. She lists the advantages: a monthly income starting at 300,000 rubles (3200 EUR approximately), a flexible schedule, and the ability to do this job alongside other work. She joined the field recently — in January 2025 — when a friend invited her to an agency that had contracts with “various military registration offices” and hired “managers.”

Before this, Victoria spent years working in HR recruitment. Now, recruiting for the war, she insists the job is “not hard at all.”

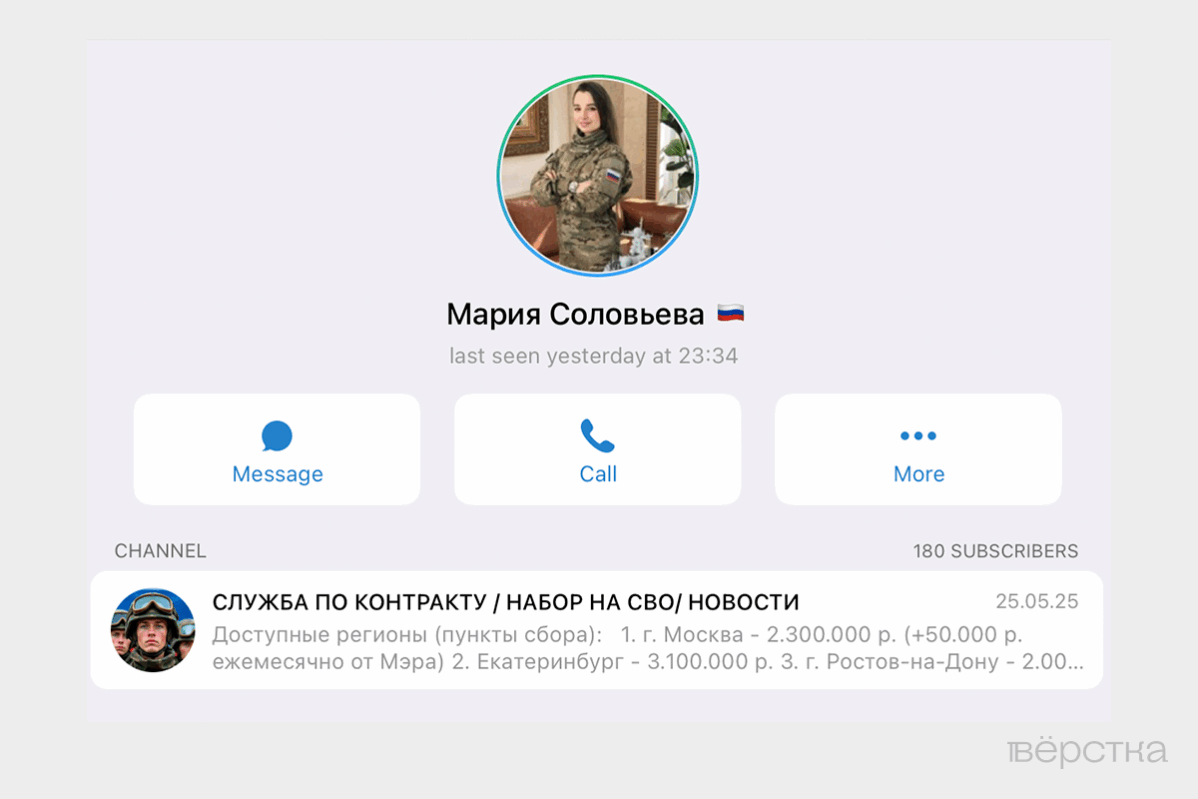

Victoria and her colleagues — other “managers” at the agency — post contract-service ads on Telegram channels and VK (Russian social network) public groups, and handle calls. Every day, they compete with dozens of other agencies for the same pool of potential recruits.

“Victory is near — hurry up and claim all the benefits and payments!” — Ivan.

“We offer individual support and security!” — Arina.

“Calls accepted from 9 a.m. to midnight. Message me anytime.” — Oleg.

In one of the largest Telegram groups advertising contract service, recruiters posted 7,945 such ads in just nine months.

“You see, a guy comes to the enlistment office, and they tell him right away: ‘Well, John Doe, forget it — you’ve been sold for this much, and now you’re ours,’” says recruiter Elizaveta. “So the candidates understand immediately that we supposedly get paid for them.”

“But you do get paid, right?”

“Well, of course — it’s recruitment. Same as hiring IT specialists or shift workers after rotations. It’s no different here.”

Victoria says she has already grown used to “difficult clients” and “completely insane” men. But she insists she’s satisfied with everything — her only regret is not starting sooner.

“If I had known about this earlier, I would’ve been earning money here long ago. Ten times more than at my main job,” she says in a voice message, sent while walking. She ends by saying she can discuss details later — she’s flying on a vacation to Turkey for two weeks.

“The amount of remuneration for the Contractor for each Candidate”

Recruitment managers rarely disclose the names of the companies they work for — or the clients they deliver recruits to. They also tend to avoid naming exact earnings, offering only a broad “range” of fees.

“From 100,000 (almost 1100 EUR) to 150,000 (approximately 1600 EUR) rubles per candidate, depending on the enlistment office,” Victoria says.

“From 50,000 (slightly more than 530 EUR) to 300,000 (3200 EUR approximately) per person,” her competitor Elizaveta claims.

On the government procurement website, Verstka found four tenders from companies that openly seek help in supplying volunteers for the war. Three of the applications were submitted by the Khanty-Mansiysk (a city in Western Siberia) City Electric Networks.

The company is prepared to spend a total of 15.5 million rubles (more than 165 thousands EUR) on the service of “searching for and selecting candidates for contract military service.” Procurement documents specify two fixed “amounts of remuneration for the Contractor for each Candidate” — 150,000 (approximately 1600 EUR) and 190,000 rubles (more than 2 thousands EUR). Their budget would cover sending 90 men to the enlistment office.

Verstka also noted that these tenders appeared immediately after the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug (a region in Western Siberia) raised its one-time military signing bonus to a national record — 3.2 million rubles (almost 35 thousands EUR).

Another tender for “candidate selection services” was announced by the Alexandrovsky City Trade Market in the Vladimir region (a region in Central Russia close to Moscow). On May 28, it signed a one-month contract with the “Voevoda” military-patriotic training center. The fee: 300,000 rubles (3200 EUR approximately) per recruit.

“The services shall be deemed properly rendered if the Candidate arrives at the place of military service,” the contract states.

Financial filings show that the Voevoda center’s revenue surged in 2024, when it began actively posting contract-service job ads across the Rostov region (a region in Southern Russia), Krasnodar Krai (a region in Southern Russia), Tatarstan and Bashkortostan (regions between the Volga river and the Ural Mountains). After reporting a 604,000-ruble (approximately 6,5 thousands EUR) loss in 2023, Voevoda turned a profit of more than 46 million rubles (almost 500 thousands EUR) the following year.

“Do you need any staff?” Verstka asks Victoria, the recruiter.

“You know, it’s competitive here — everyone’s on their own,” she replies. “You teach yourself, you look for Telegram channels where you can post. You have to persuade people so they come to you and not another recruiter. No one trains you, that’s just how it is.”

To start earning from recruiting, newcomers generally have to register as sole proprietors, learn the advertising market, and be ready to invest their own money. Posting ads on large Telegram channels can cost tens of thousands of rubles.

For 45,000 rubles (almost 500 EUR), for example, administrators will publish a recruiter’s ad in hundreds of city groups disguised as job-seeking communities — “Work in St. Petersburg,” “Jobs in Voronezh Region,” and others — which in fact promote “SMO” enlistment. Each ad appears 30 times, but its effectiveness is almost impossible to measure.

“I spent more than 100,000 rubles (almost 1100 EUR) on advertising this month, and got no response at all. My posts get buried instantly under thousands of similar ads. It’s a lottery — pure luck. I hope the silence is just because of the May holidays,” Victoria complains.

While professional recruiters fight for a shrinking audience, some regions now offer ordinary residents the same recruitment fees. Without spending money on advertising or registering as an entrepreneur, anyone can earn 100,000 to 200,000 rubles (1100—2150 EUR) simply by bringing acquaintances — not strangers — to the enlistment office.

“When he leaves, you’ll get the receipt”

“You don’t have to come with him. He’ll just say, ‘My sister brought me.’ Or whoever — his wife? And he’ll write a statement himself.”

An employee of the Yaroslavl (a region in Central Russia) military registration and enlistment office picks up the phone at the end of the workday and explains the terms of the local referral program, which people jokingly compare to a “bring a friend” promotion. The region initially offered 30,000 rubles (approximately 320 EUR) — later increased to 100,000 — to anyone who “brings a volunteer to the enlistment office.”

“And I don’t even need to accompany him?” Verstka asks.

“That’s right. He’ll list you in the application, in his own handwriting. The application is approved first by our selection committee, then by the administration. After that, you’ll get a call, come to the administration, sign the paperwork, and that’s it — the payment will come within a week.”

“Do I need to prove I actually brought him?”

“No, nothing like that. The only thing that matters is that he’s accepted into a military unit. It’s better if he gets tested in advance — syphilis, hepatitis, HIV, tuberculosis. But all of that is free.”

The military registration office in another city, Ulyanovsk (a western Russian city) — where referral payments are part of a social program called Care — has stricter rules. You cannot “bring” a recruit without accompanying him in person. The compensation, however, is higher: 150,000 rubles (approximately 1600 EUR).

“You just need to keep an eye on him,” an employee explains. “Go through the medical checks with him, stay until he leaves. And once he leaves, you’ll be given a receipt. You take it to the administration — and that’s it.”

“Does it matter who he is to me?”

“No, it doesn’t matter at all. The payment comes in two weeks at most.”

“So I just come, wait while he gets examined, and that’s all?”

“Yes, that’s basically it.”

In February 2025, the Ulyanovsk region allocated 7 million rubles (more than 75 thousands EUR) to the Care program; in April, another 19 million (more than 200 thousands) were added. In May, the region arrested former Deputy Minister of Property Relations and Architecture Alexander Taushkin. According to investigators, he and a subordinate submitted a fabricated list of 12 recruits to the Ministry of Social Development and collected 1.8 million rubles (almost 20 thousands EUR) in referral payments.

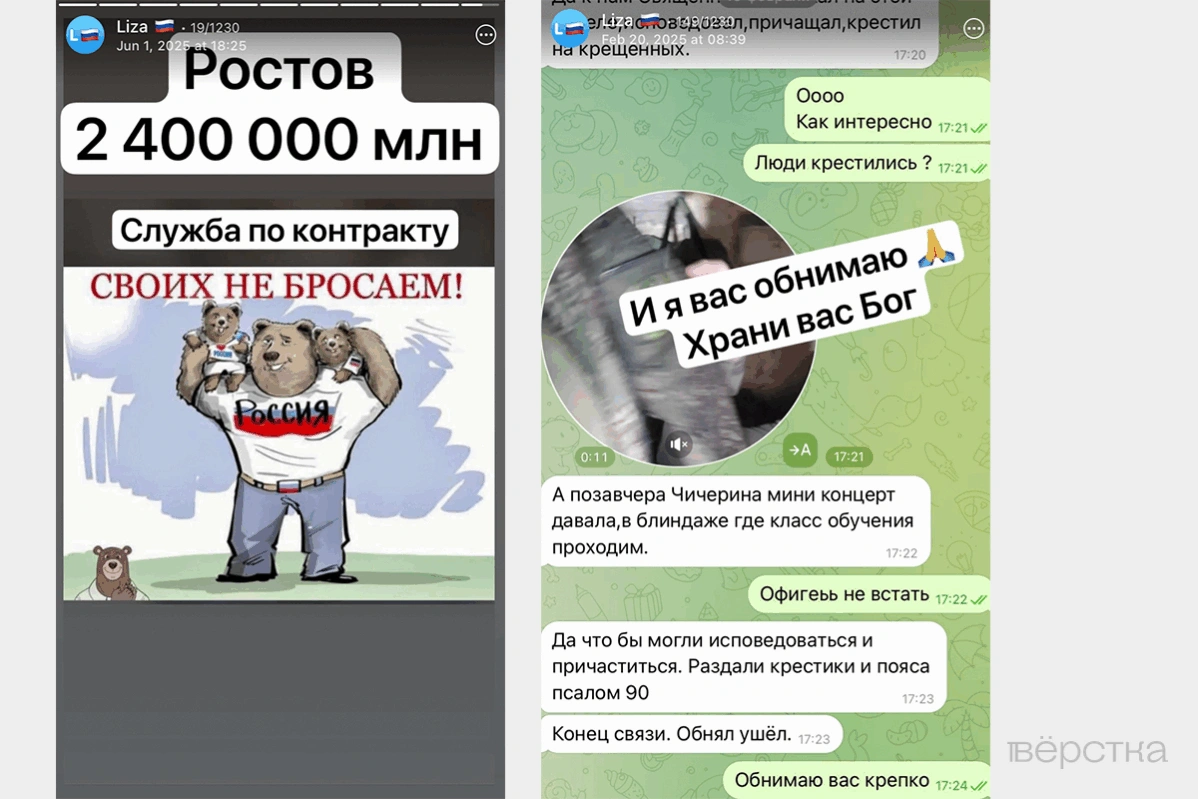

Only a few regions — including Tatarstan and Bashkortostan — have publicly announced referral programs. Yet enlistment office employees say such schemes still operate quietly “in many places,” and Russians “often” receive payments for bringing in relatives.

But some people take their brothers or husbands not to official enlistment offices, but directly to recruiters they find through online ads — expecting no compensation at all.

“That’s what they write,” recruiter Elizaveta tells Verstka: “‘Please take him — he’ll drink himself to death here, but at least he’ll die with pride there.’”

Elizaveta has been sending men to the front for more than a year. She insists she works “honestly” and even tries to dissuade candidates she believes are not ready for war.

“I don’t want to pretend to be a saint”

Liza (short for Elizaveta) has built her personal brand as a recruiter around what she calls a “human approach.” She says that, unlike many of her colleagues, she stays in touch with the men she recruits, talks with their families, sends soldiers money for cigarettes, and is even willing to deliver phones or tablets to them without asking for repayment. And for those who romanticize the war, she shows videos of evacuations — “with bodies, with shattered heads.”

“Online, they write: ‘Oh! You want to be a driver? Come on, come on, you’ll be driving generals around.’ And then they change his clothes, take his phone, and throw him straight into battle. Today I talked one guy out of it. He asked, ‘Is it true they train drone operators in Yaroslavl?’ I told him, ‘Yes, but it’s not a 100% guarantee.’ ‘What do you mean?’ he said. And I explained: they can buy out your assignment along the way and transfer you to the assault troops if needed. I don’t want to pretend to be a saint, but I’m not ready to live with that on my conscience — that’s dirty money,” Elizaveta says. Still, she notes, “three out of five” candidates she works with end up going to the front.

She posts screenshots of her conversations with recruits on social media — asking them to check in every week, making sure they’ve received their payments, and getting them to promise they’ll return home.

“Give me your word: finish your contract and we’ll meet in Moscow. How does that sound?” she tells one new recruit.

He promises he’ll meet her “if he survives until leave.” He likely doesn’t know she hasn’t lived in Russia for years.

Alongside posts in recruiter channels, Liza’s messages also appear in Istanbul expat group chats. She is looking for an apartment with two bathrooms, a breakfast café with a nice view, a Russian-speaking speech therapist, and a club for her two-year-old son.

During our phone interview, Liza is repeatedly interrupted by the boy, who doesn’t yet attend kindergarten. She says she sympathizes with the women who are left alone at home when their husbands go to war.

When Verstka asks whether she regrets anything from the past year, Liza doesn’t hesitate: “Yes, yes — at least three cases.”

“The first was a foreign citizen. He signed the contract, went to training, and got scared. He kept writing to me: ‘Elizaveta, please help me break my contract. My mother had a heart attack, so I have to fly to Uzbekistan.’ And I realized there was nothing I could do.

The second was a very young boy. I tried to convince him to take a shift job instead of going to the army, but I failed. Three weeks later, he wrote: ‘I’m scared.’ And now, a year later, he hasn’t logged into WhatsApp or Telegram.

The last one was a father of several children who went to the war without telling his family. He left for work in the morning and stopped answering calls. His wife noticed his slippers and towel were missing from the bathroom.

His wife and his mother — who had just had heart surgery — started calling me: ‘Liza, what are you doing? Why did you send him there?’ I tried to convince him to come home, but he replied, ‘Block my whole family.’ A month later, we were told he was missing. And the children were waiting for him for New Year’s.”

These cases made her question herself, she says. She often thinks about the “boomerang of life.”

“When another soldier went missing, I stopped advertising. I’m definitely taking a break right now,” Liza tells Verstka.

A week later, her contact details reappear on one of the largest Telegram channels promoting contract service.

“Thank you, our heroes!” she writes, promising potential earnings of more than six million rubles a year.

Since last September, Liza has advertised her services 160 times.

Cover: Dmitry Osinnikov

Anna Ryzhkova, with the participation of Ivan Zhadayev

Поддержать «Вёрстку» можно из любой страны мира — это всё ещё безопасно и очень важно. Нам очень нужна ваша поддержка сейчас