Tattoos, Teeth, Crosses: Inside the Morgue Identifying Russia’s War Dead

What the Rostov morgue looks like in the fourth year of the war — according to staff and grieving families

“Branch of Hell.” “Road to Paradise.” “Last Refuge.” These are the phrases volunteers and soldiers use to describe the morgue where the bodies of Russian servicemen have been arriving since February 2022. Hundreds of people come each day to the 522nd Center for the Reception, Processing and Dispatch of the Deceased in Rostov, hoping to find their missing relatives by recognizing a familiar tattoo, scar, or tooth.

Some names have been altered or omitted for safety. Spellings reflect how sources provided them.

This report includes graphic descriptions and photographs from inside the morgue.

To read future texts, follow us on Telegram

“Well, in short, I send them on their final journey”

“I carry the bodies, dress them in military uniforms, lay them in coffins, attach their insignia. To collect DNA, you cut the skin and separate the tendon. You take a saw and cut off a few pieces, three or four centimeters long. So yes, I send them on their final journey.”

This is how 40-year-old mobilized soldier Sergei describes his work at the Rostov morgue. He does not like discussing his service, he says he does not want to “shock” people, but admits that anything is better than the front line.

“There,” he recalls, “it’s worse when you’re carrying a wounded guy and he dies right in your arms.” Here, in a major southern city, he says, the conditions are “normal” and the salary is 210,000 rubles (approx 2350 EUR).

What is the 522nd CRPDD in Rostov-on-Don

The 522nd Center for the Reception, Processing, and Dispatch of the Deceased in Rostov (CRPDD) is the only specialized military unit in Russia responsible for handling soldiers killed in armed conflicts: receiving the bodies, preparing them, and sending them home.

The unit was formed in the 1990s; during the First Chechen War, the bodies of Russian servicemen were brought here, where conscripts prepared them for shipment. A report on Russian television at the time noted that soldiers serving in this unit were allowed to file for discharge “on the very first day.”

Since spring 2022, during the war in Ukraine, the CRPDD has become the main facility receiving the bodies of Russian servicemen killed in the so called “special military operation” (SMO). In April 2024, the morgue relocated to a larger site equipped with new infrastructure designed to manage the increased flow of families coming to identify remains and provide DNA.

“People are such scum, you get used to anything,” Sergei says. “So send him here. He’s a man, not a weakling.”

A Verstka correspondent wrote to Sergei, posing as the sister of a conscript due to serve in Rostov-on-Don, to initiate a conversation about one of the most secretive military units in Russia. Most of Sergei’s colleagues—conscripts, contract soldiers, investigators, medics—are reluctant to talk about their work in the main military morgue.

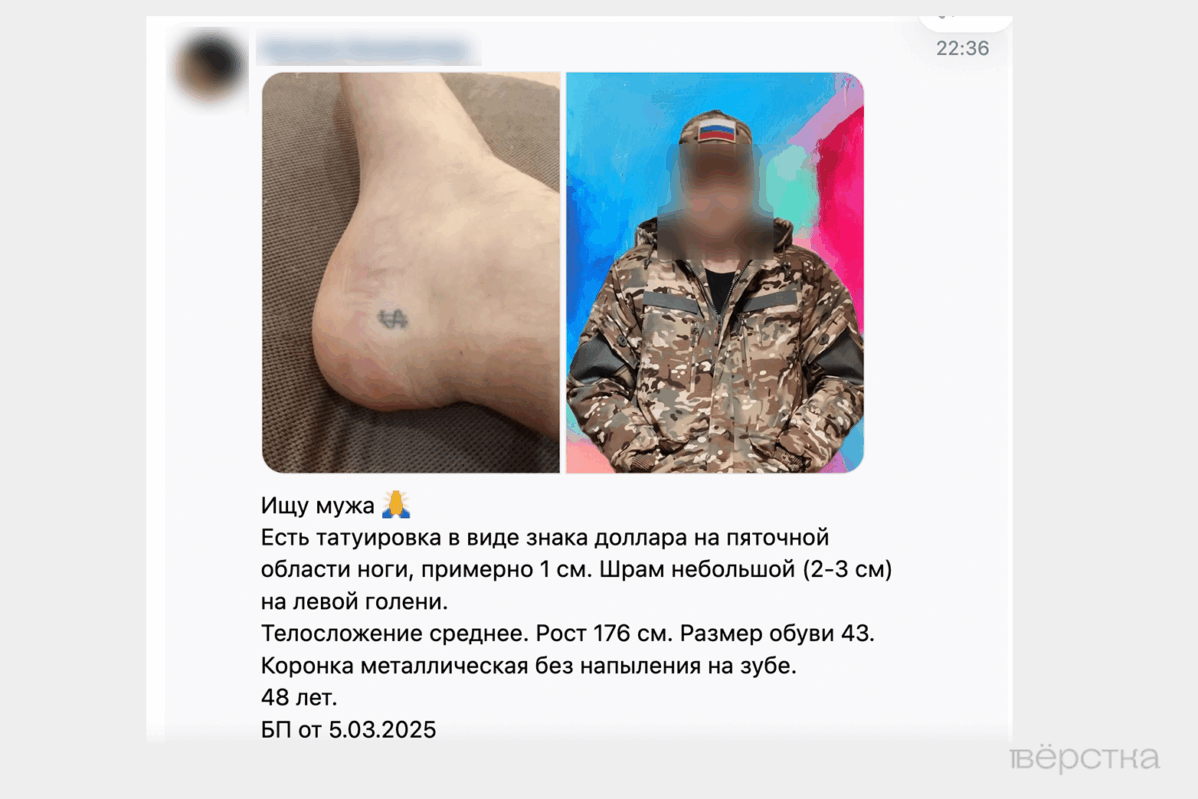

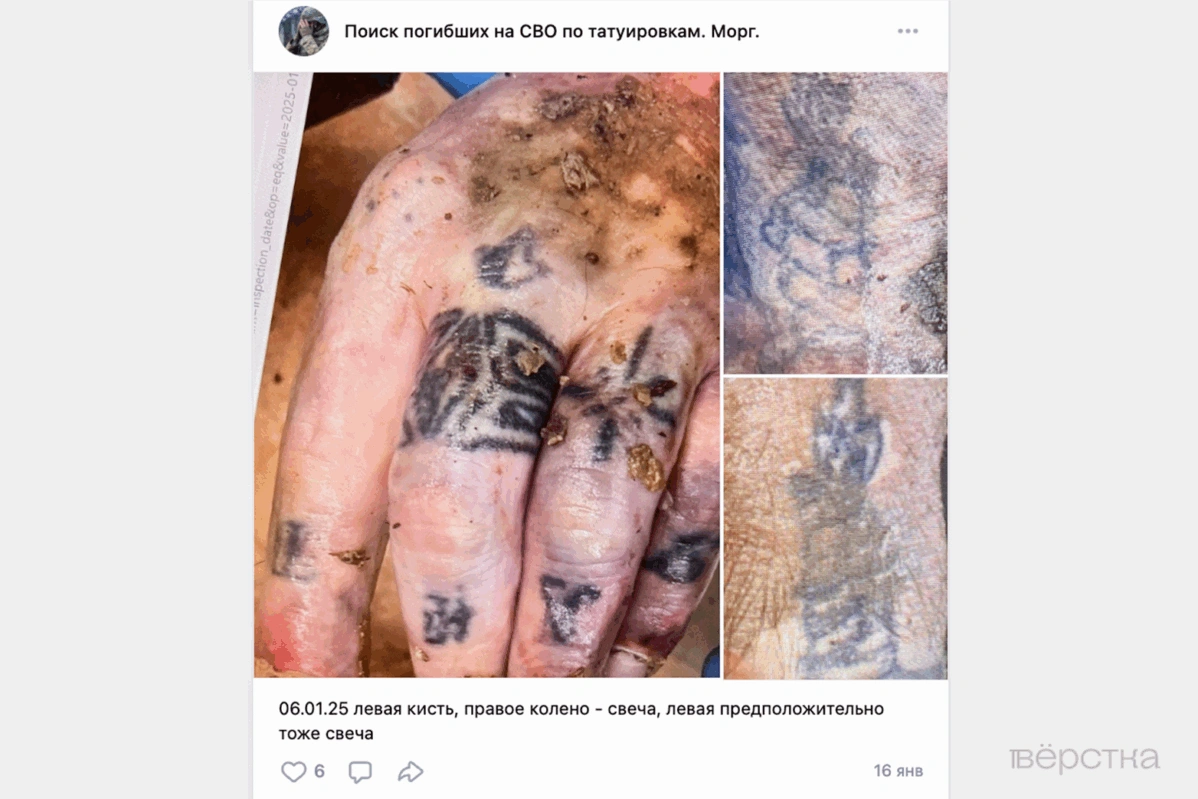

Photo: VKontakte group “Search for the Deceased in the SMO by Tattoos. Morgue.”

“Not in our time. You can’t talk about that. It’s a military secret,” says Igor, who arrived in Rostov for a two-week assignment and ended up staying for a year. In a volunteer chat, he asks volunteers for heavy-duty gloves and printer parts.

“I don’t think it’s worth talking about,” writes Denis, a soldier who spent nine “difficult” months at the morgue. “I’ve already left, but they really need gloves.”

“My schedule is so tight that I don’t think I’ll be able to find time for an interview in the near future,” their colleague Julian tells Verstka, explaining his refusal.

As an administrator in the Telegram group “Search for Missing Servicemen” (127,000 members), Julian posts similar notices: height, shoe size, detailed descriptions of tattoos — all belonging to soldiers whose bodies have not yet been released to relatives. Some entries are later updated with the word “identified.”

“If the documents are nearby, they’re placed in a bag with the deceased”

Julian, who works at the morgue, truly has more than enough to do. While relatives search for missing soldiers and publish 500–600 requests every day, he works in the opposite direction: he searches for the relatives of the dead. His job is to compile descriptions of the bodies brought to the morgue.

Arrived, presumably, from the Donetsk direction. Height ~170 cm, shoe size 42. Tattoos:

Inside left forearm: “I live, I create, I laugh, I dream.”

Height approximately 175 cm. Tattoos:

Right side of neck: a swallow.

Left inner forearm: a clock face with Roman numerals, a flower, and, presumably, the word “family” at the bottom.

Right arm: a girl, dice, a $100 bill, a gun, bullets, and bullet holes.

Soldier believed to be from the Donetsk region. Short, approximately 160 cm. Tattoos:

Right shoulder: an abstract pattern.

Outer right forearm: the inscription “spasi i sokhrani” (“save and preserve”).

<…>

“Isn’t this the same lettering for ‘save and preserve’?” asks Victoria from Omsk, attaching a cropped photo where her husband’s arm is enlarged, the tattoo clearly visible. In the picture, her son is holding the man’s hand.

“Victoria, that’s not a forearm,” the chat administrators reply. They urge her to read the tattoo descriptions carefully. “If one fragment matches but the rest does not, then this is not your soldier.”

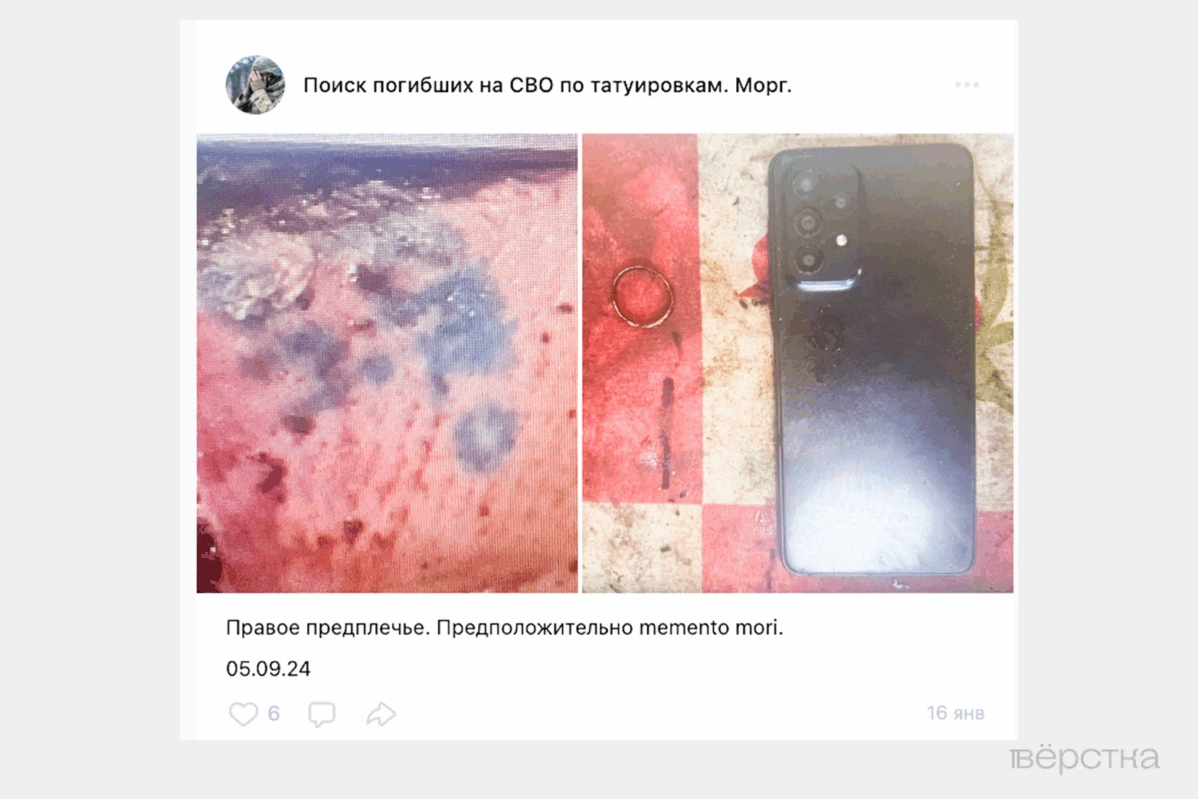

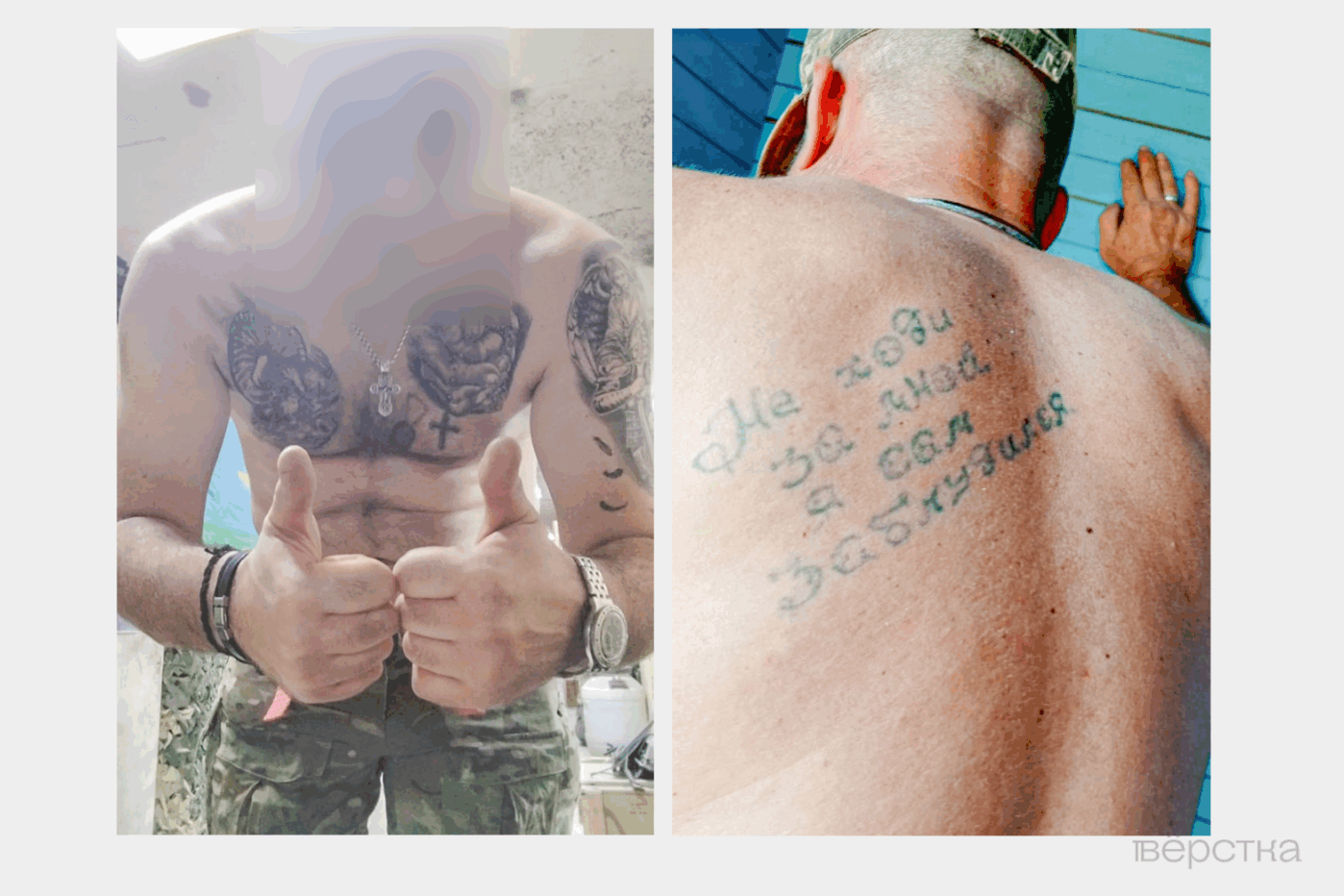

Relatives of the missing, most often wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters, spend months waiting first for a phone call from their soldier, and later for an invitation to identify a body. Alongside lists of prisoners, they now sift through photographs of faces, hands, feet, fingers, and other body parts with identifying features. These photos began circulating privately among families in early 2025, shared by employees of the Rostov morgue and posted in closed groups. Some images also show personal belongings recovered with the body—items that survived long enough to be transported from the battlefieldi.

January 16, 2025. Four women immediately recognize a scorched chain with a cross and a watch case that were brought to the morgue along with the body shown in a photo.

“How can I reach you? I have doubts about the length of the chain,” writes Svetlana from Yaroslavl (a city in Western Russia), who is searching for her husband.

“This was the only thing our soldier had with him, and I’m not sure about the size of the cross. He didn’t have any tattoos,” says Marina from Cherepovets (a city in North-Western Russia).

“My husband had the same watch, the same chain, and a wedding ring. There’s a red star on his dog tag. My husband went missing at the end of October,” writes Yulia from the Jewish Autonomous Region (Russian Far East).

“Hello! Was there a wedding ring and a chevron that said, ‘My wife told me to take care of myself’?” asks Oksana.

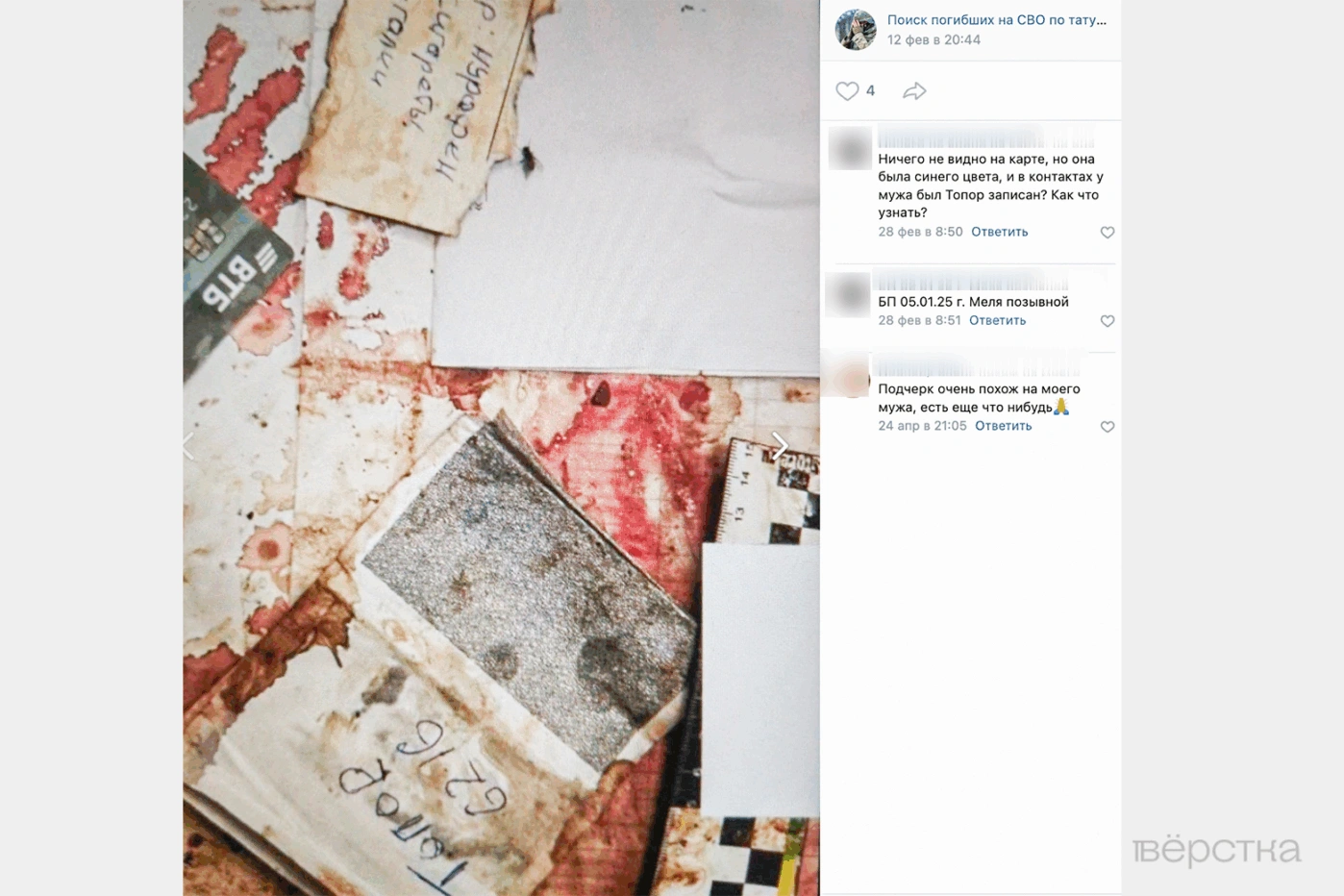

February 12, 2025. The corners of the military ID are smeared with dirt or singed; the stamp has run across the paper, making most of the text unreadable — only the name Ilya can still be made out. The soldier was taken from an “unknown” location without any personal belongings in early 2025. A morgue employee photographs the document: fingers in blue medical gloves press the warped pages flat against the table.

Alongside him, other unidentified soldiers from Ukraine were returned with “Mir” (a Russian card payment system) cards, small religious icons and amulets on strings, 100- and 5,000-ruble notes, mobile phones, and scraps of paper bearing call signs or handwritten lists — “Painkillers, cigarettes, lighters.” The items were photographed on metal tables still marked with bloodstains. All of their owners arrived at the morgue around Orthodox Christmas time, on January 6.

“Everything has to be collected into a bag, packed, and taken to ground zero,” explains Viktor, a soldier who regularly picked up “cargo 200” (a military slang for deceased) from the Rostov morgue and accompanied the bodies. “If documents are nearby, they’re placed in the bag with the deceased — the black ones with zippers. Each person is packed separately, all the remains.”

“Insoles that make your eyes water from the smell”

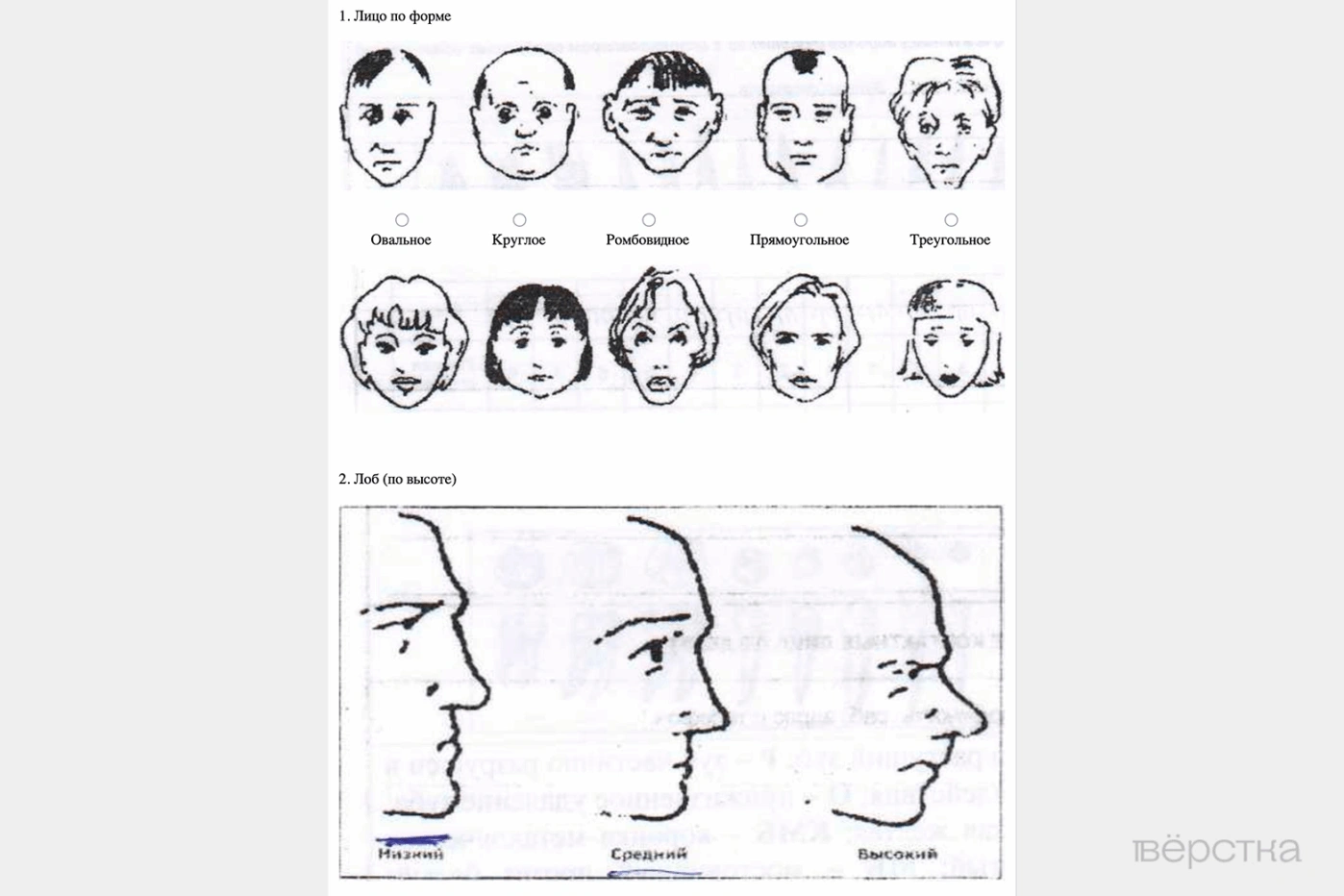

Women decipher handwriting on damp, faded scraps of paper, compare tattoos in photographs, and fill out forms with detailed descriptions of appearance — down to dental records — in case morgue or hospital staff ever find a match.

— Noticeable tattoos across the body; a dimple on the chin.

Bald patch on the head; shoe size 46.

Tall, with a stocky build.

Scars from self-inflicted cuts on one arm, partially covered by a tattoo of a ship.

Tattoo of an eagle’s head on the shoulder.

Tattoo on the back with the inscription: “Forgive me, Lord, for my mother’s tears” (or “Forgive me, God, for my mother’s tears”).

Slender build, approximately 170 cm tall.

Scar on the bridge of the nose; small scar above the right eyebrow.

The name “Natalia” tattooed on the ring finger.

Tattoo on the lower right side: folded praying hands with rosary beads and an inscription about seeking forgiveness from his mother.

To speed up the identification process, relatives submit DNA samples through private laboratories and send them directly to the morgue. If a missing soldier has no blood relatives, families search for household items that might contain biological traces — toothbrushes, razors, combs, or even shoe insoles “that make your eyes water from the smell,” as staff advised Tatyana from Rossosh (a city in Southern Russia).

In February 2024, another woman from the Amur region (Russian Far East) mailed strands of her adopted son’s baby hair — “cut in infancy” — along with his silver cross and chain for DNA typing. Months later, having received no reply, she wrote again, worried that the hair contained no follicles and that the chain, which her son had not worn in years, carried no sweat residue. When this request was also ignored, she decided to petition the court to have her adopted son declared dead in order to receive a pension and erect a memorial in his hometown, even without a body. The court granted her request and officially set the date of death she proposed.

Many relatives who cannot reach the military units or the Ministry of Defense hotline eventually buy tickets and travel to Rostov-on-Don themselves. Early each morning, they line up outside the CRPDD entrance, waiting to receive a ticket for a meeting with a military investigator.

“Think of it as going to the store”

The Center for the Reception, Processing and Dispatch of the Deceased consists of a morgue building and the surrounding grounds, where several trailers have been set up to manage the flow of visitors. Volunteers guide families through the process:

Trailer No. 1 is where people fill out a search form listing tattoos, scars, dental features, and other identifying marks. Trailer No. 2 serves as a waiting area. Trailer No. 6 is for submitting DNA samples. Before meeting with investigators, relatives go to Trailer No. 3; the investigators themselves work in Trailer No. 5, where they search the database, show photographs of bodies, and compare distinguishing features.

At the morgue, where families wait their turn, doctors and psychologists are on duty, and one can grab tea and cookies for a quick snack.

“It’s organized well, if it is an appropriate word here,” says Natalia, who was 102nd in line to enter the trailer where investigators work. “They explain everything and guide you through the process.”

None of the identifying features matched her husband, and Natalia returned home with the hope that he was still alive. While she was inside, someone “who seemed to be a volunteer” played with her son and showed him some cartoons to distract him.

“If you start crying, they won’t let you in,” says another woman, Ekaterina from Kaliningrad (a city in Western Russia), recalling her trip to Rostov. Her husband’s body was found in the morgue under someone else’s documents.

“If you go there expecting to throw a fit, there’s no point,” says Tatyana from Rossosh about her visit to the central military morgue. “And not because, as some might say, you didn’t love your husband — no. You just have to approach the situation soberly. You can cry and scream after the funeral. A morgue is a morgue. Treat it like going into a store: a place where you have to do something temporarily. It’s just a part of your life that you get through.”

Tatyana recognized her husband in the first photo investigators showed her. Others are forced to look through several images of strangers before receiving an answer.

“Everything looked similar,” says Elena, who was called to Rostov to identify a body by its tattoos because she couldn’t describe them precisely in words. “But none of them were our soldier.”

Before families travel to the central military morgue, volunteers warn them to prepare for “psychologically difficult” images. They emphasize that civilians are not allowed inside the morgue itself — identification is done in a trailer, on a computer screen.

“But we went straight to look for him among the bodies,” says Dmitry, a contract soldier who traveled to Rostov on assignment to retrieve “cargo 200.”

He recalls how, in the spring of 2023 — before the morgue was reorganized into separate zones — he identified the “relatively intact” body of a colleague lying in a corner of the hangar.

“It’s a branch of hell there”

“Bodies laid out in rows. They tell you, ‘He’s somewhere in that corner — go have a look.’ The thing is, even when a soldier has already been identified, the commander still requires you to confirm that it’s really your man. I knew this guy personally, so it was immediately clear it was him,” says Dmitry.

He adds that, to his surprise, he saw conscripts working in the hangar — they were the ones placing the body into a coffin and preparing it for transport home.

“He looked good, and there was that little viewing window in a coffin,” the soldier says of the deceased. “They asked us if we had a uniform. We said yes. They dressed him, checked how the makeup looked, and that was it — placed him inside, sealed the coffin. First the regular one, then the zinc one.”

Dmitry spent two days on that assignment. He remembers the weather in Rostov being warm — he was already wearing shorts — but inside the morgue it was cold because of the refrigeration units. He also recalls that, two years earlier in the hangar, he saw a civilian man who had been let inside to identify a soldier. Dmitry is convinced the man was the soldier’s father, because he “looked like he was about to pass out.”

Looking for my sons.

[Call sign].

On his left arm, he has an unfinished tattoo of an eagle’s head covered by a wing. Medium build. Missing tooth in the upper front row. Shoe size 40. Born [date of birth]. Went on a combat mission on May 31, 2025; missing in action since [date].

[Call sign].

Scar from an appendectomy on his stomach and three scars from knife wounds. Shoe size 41. Born [date of birth]. Missing since May 31, 2025; last contact on [date].

Looking for my son, [full name].

Born [date of birth]. Went on a combat mission on 12/28/2024; missing since [date]. Height 187 cm, shoe size 43. Tattoos: a cannabis leaf on the left side of the neck; a moon on the back of the head; an angel and a devil on the collarbone; Death with rosary beads on the forearm; the Latin inscription veritas lux mea under the ribs. <…>

The inscription on his feet “poprobuy dogoni” (“catch me if you can”), a scar above the right eyebrow from a wound, a bullet scar on the left shoulder, and knife scars on the left arm.

Last known location: Raigorodka.

Nothing in the morgue felt truly “shocking” to Dmitry — until he stepped outside “to smoke, to think,” and saw a Ural truck pulling into the compound.

“An ambulance arrived while we were there. The doors opened, and there were about forty bodies piled on top of each other. They were lying just as they had been brought in. They carried them inside.”

These trucks are used to transport the dead from the front lines to the morgue. Among the bodies may be those who died a week earlier — or those who could not be retrieved for more than a year. Remains that have been left in the combat zone for a long time also end up stored in the morgue. According to families, DNA analysis from bones, when no soft tissue remains, can take anywhere from several months to a full year.

When Dmitry’s assignment in Rostov ended and he had to return to his unit in one of Russia’s eastern regions, he was asked to take his colleague’s body with him — and to escort 14 more dead soldiers home because there weren’t enough escorts. After that trip, he never returned to Rostov on duty.

“It’s a branch of hell there,” he says.

His colleague from another region, Viktor, who accompanied “cargo 200” for several months, puts it differently: “There’s nothing terrible there except the smell.”

“You can’t describe it,” he says. “It’s just the smell of corpses. Imagine a regular refrigerator with food in it. If something inside goes bad, the smell spreads to everything else. It’s pretty much the same there. You arrive, you stay a while, and afterward you wash your uniform. Then you wash it again. Because the smell sticks to you.”

In June, morgue staff added a mango-scented aroma diffuser to their list of requested humanitarian supplies — alongside drinking water, chlorine tablets for disinfection, and basic office items.

“There was an option for delivery by car”

Contract soldier Viktor speaks with Verstka during a break between medical procedures: the lower third of his shin has been blown off, the stump has only recently healed, and he is now waiting for a prosthesis and then a medical discharge.

Viktor says he “saw everything” on the front line. When the conversation shifts to civilian life, he suddenly complains about the “alcoholics and drug addicts” he encounters in the hospital — people he believes “could have just been shot” at the frontlines. He makes it clear that after the war, he became “almost indifferent” to his assignments at the Rostov morgue.

While families crowded outside the CRPDD building searching for and identifying bodies, Viktor handled the routine logistics: paperwork, phone calls, arranging transportation and burials.

“They were flown out by plane, or—if it wasn’t too far and there was the option to deliver by car—a hearse would come,” he explains. “And I’d drive around the region to handle everything.”

“Please take my brother off the search list — our war is over. He was identified today.”

“Us too. The plane arrives tomorrow. We’ve been waiting since 2024 — finally. Wishing everyone good luck, may your soldiers come home alive.”

“Please remove my father-in-law from the search, he’ll be home on Tuesday. Now we just have to find my husband — hopefully alive.”

After talking with conscripts in the morgue’s smoking area, Viktor says he got the impression that some even want to serve in the CRPDD because the pay is higher. “And at the end of their service, they even get some awards,” he adds. Sergei, who was mobilized, says conscripts assigned to the morgue’s military unit “live like pigs in clover.”

Verstka found several conscripts who had been stationed at the Rostov morgue through photos on VKontakte (a Russian social network) — a few young men had posted mirror selfies from the barracks in the building next door.

One of them, Ruslan, says he asked to be transferred to the morgue after several difficult weeks “in the regiment,” where conditions were “harsh.”

“I didn’t care where I ended up, as long as it wasn’t there. There’s more freedom here,” he says. “But there are also regular soldiers who were assigned here from the start. There are more than a hundred of us conscripts.”

Ruslan says he can’t go into detail about his duties, but conscripts are entrusted with “a lot of responsibilities.” Psychologically, he says, it doesn’t bother him: “I’m used to it.”

“They work with the bodies,” his mother explains to Verstka. “They load them into the morgue. They bring them in bags and check the tags to see who goes where. It’s okay, he says — he’s used to it. They even eat next to them now,” she adds with a laugh.

Sergei, a mobilized soldier who has been working with bodies in the morgue for two years without days off, talks mostly about money.

“For that kind of salary, anyone would do what I do. You get used to everything. I’m fine with looking at dead bodies — and with the smell that comes with it. Being here is stressful, sure, but I’m holding on until the end.”

“When will it all end?” Verstka asks.

“Ask Putin. Send him a letter,” he replies.

Sergei can’t clearly explain how he copes with the stress of his work, so Verstka scrolls through his social media. In his photos, he’s either holding a machine gun, wearing a gas mask, or in a white coat thrown over his military uniform.

He posts a patch that reads, “This is the best job in the world,” and follows meme communities like “Joker,” “Painfully Funny,” “Humor Wave,” and “The Paradox of a Good Mood.”

In the evenings, the morgue worker writes to dating groups on Telegram in Rostov, inviting women to go for a walk, “kill the evening,” or “a place to crash for a meow (slang for mephedrone)”.

“I would recognize them even by their teeth”

In a closed group for relatives of the missing — where photos of bodies with tattoos and personal belongings from the Rostov morgue are shared — women are invited to join two chats.

One is strictly for search requests if someone is still being looked for, and for condolences if they have been identified. It currently has 1,805 members.

The second is for “communication and support.” There, women discuss the identification process, scammers, depression and insomnia, court battles over “coffin money” (a reimbursement for a killed in action relative) and the presidents of Russia and Ukraine — day and night.

Some of the messages read:

- “We’ve written to Putin and everywhere. All the same words: ‘Taken under control.’”

- “Now I’ll bury him, and soon I’ll lie down next to him.”

- “They didn’t find anything on the razors, and they don’t take insoles. You know why? They need living flesh.”

- “If anything, everyone here wears shoes like this. And no one whines or complains.”

- “This is war. If we don’t win it, then why the hell did we start it?”

- “This war has changed us all — may it be damned three times over.”

Sometimes long voice messages appear in the chat — difficult to understand because the sender’s voice trembles or breaks into sobs. At the end of May, one of these messages was recorded by Svetlana, whose husband went missing in January 2025.

“I thought I was losing my mind. I waited and waited for them to bring him back so I could bury him, go to his grave. <…> And when they opened the coffin, three people said at once: ‘Where’s Dima? This isn’t him,’” she says through tears. “And there was a boy lying there. His face was so clean. He must have died recently. His legs were gone — half a person, that’s all.”

Before the funeral, Svetlana insisted that the coffin be opened. She even threatened the attendants: if they didn’t let her see the body, she would “hire some drunks to dig it up” at night.

After the coffin was opened, she began showing the officials photos of her husband — from childhood, from school, from the army. Finally, she asked them to roll up the body’s sleeve to check for a tattoo. The skin was unmarked.

According to Svetlana, the coffin was then returned to the Rostov morgue, and she allowed herself to hope again.

“Maybe he’s a prisoner of war? My hope fades a little more every day, but I’m still waiting. And if he died, then let them bring him back. Even if they tell me everything matches down to the last detail, I’ll still have the coffin opened. No matter how much time has passed, I’ll recognize him. Even if it’s just a piece of his uniform — I’ll still recognize him. Even by his teeth, I’ll recognize him.”

Svetlana sends her eleventh voice message, crying.

“Svet, you need to calm down,” another woman in the chat replies. “Soon your son will be graduating from kindergarten — his mom should be the most beautiful one there.”

Victor, a contract soldier who has accompanied coffins from the Rostov morgue to cemeteries several times, says families almost always want to see the body — even if it has been lying in the open for a long time and is severely deformed. Before burial, they “look through the little window” left in the coffin, provided the face is still intact.

“The mother was in terrible shape, and so was the wife — they kept fainting,” he recalls of one trip. “You doubt right up until the last moment, and then you see the face and understand: it’s him.”

“What did you usually say at the funerals?” Verstka asks.

“It was the standard speech… an irreplaceable loss for the army and for the family. Such-and-such military unit expresses its condolences to the relatives of the deceased, and so on, blah blah blah…”

Cover: Catherine Popov

Поддержать «Вёрстку» можно из любой страны мира — это всё ещё безопасно и очень важно. Нам очень нужна ваша поддержка сейчас